What Herschel Found in a Dark Cloud

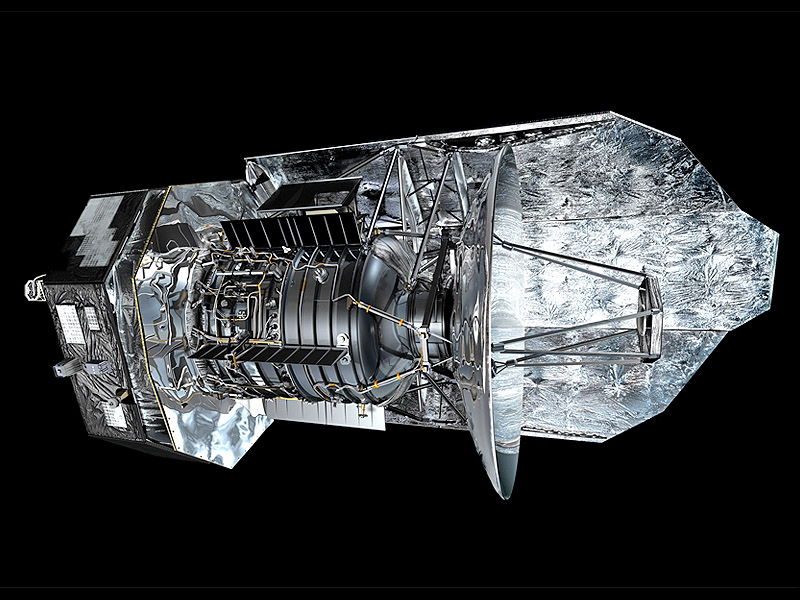

The Herschel Space Telescope [ESA/AOES Medialab, via Clarksville Online]

A thousand light years away in the constellation of Aquila the Eagle lies a great dark cloud. This cloud (called a nebula) stretches between the stars for some 65 light years - that's over sixteen times the diameter of our solar system.

Dust completely conceals the interior of this nebula. At least it did until the end of 2009 when the Herschel Space Observatory was able to penetrate the dust to photograph it for the first time. What astronomers found is a stellar nursery, a place where new stars are forming.

A dark nebula is a good place for star formation. Although the material in a nebula is diffuse, it's there in great quantities. A triggering event of some kind, such as a nearby supernova explosion, can cause the cloud to become unstable and start collapsing under its own gravity. It breaks up into fragments which then continue to collapse, becoming denser as they evolve into stars.

Inside the Eagle's nebula astronomers have found six hundred of these dense regions that will become stars. After some ten thousand years, an embryo star, called a protostar, forms in the center of the dense region, giving out heat and light. When it becomes hot enough to sustain nuclear fusion, it becomes a true star.

The Herschel Space Observatory captured this image of the Eagle nebula, with its intensely cold gas and dust. The "Pillars of Creation," made famous by the Hubble Space Telescope, are seen inside the circle. There are future stars embedded in dark filaments, and hot young stars are already illuminating the nebula to produce two bright regions. [Image: ESA/Herschel/PACS/SPIRE/Hill, Motte, HOBYS Key Programme Consortium]

But how could Herschel see through dust when other instruments couldn't?

Our eyes can't see through dust, and neither can telescopes that detect visible light. However, light comes in many wavelengths that are invisible to our eyes, including the longer wavelengths of infrared and submillimeter. These can penetrate dust, and also see the cooler part of the universe, such as the star-forming regions, which radiate at these wavelengths.

Earth-based telescopes can't detect this light because our atmosphere absorbs it. However, Herschel's sensitive instruments could see the entire spectrum of the far infrared and submillimeter radiation, the first telescope to do so.

Herschel was launched in May 2009 by the European Space Agency (ESA), the largest telescope ever sent into orbit. At 3.5 meters (about eleven and a half feet) the main mirror is 0.9 meter (almost three feet) greater in diameter than that of the Hubble Space Telescope.

The telescope was named for William and Caroline Herschel. They were German-born, but lived in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. William was the discoverer of the planet Uranus and also of infrared radiation. With the assistance of his sister Caroline, he laid the foundations for modern astronomy. Caroline, who was the first woman to be credited with the discovery of a comet, got her brother interested in nebulae. Together they surveyed the sky and cataloged the nebulae of the northern hemisphere.

The Herschel Space Observatory had been observing low-temperature objects to help us understand, amongst other things, how stars and galaxies form and evolve, and the chemistry of nebulae. On April 29, 2013 the mission ended when the infrared observatory finally exhausted its helium coolant.

A thousand light years away in the constellation of Aquila the Eagle lies a great dark cloud. This cloud (called a nebula) stretches between the stars for some 65 light years - that's over sixteen times the diameter of our solar system.

Dust completely conceals the interior of this nebula. At least it did until the end of 2009 when the Herschel Space Observatory was able to penetrate the dust to photograph it for the first time. What astronomers found is a stellar nursery, a place where new stars are forming.

A dark nebula is a good place for star formation. Although the material in a nebula is diffuse, it's there in great quantities. A triggering event of some kind, such as a nearby supernova explosion, can cause the cloud to become unstable and start collapsing under its own gravity. It breaks up into fragments which then continue to collapse, becoming denser as they evolve into stars.

Inside the Eagle's nebula astronomers have found six hundred of these dense regions that will become stars. After some ten thousand years, an embryo star, called a protostar, forms in the center of the dense region, giving out heat and light. When it becomes hot enough to sustain nuclear fusion, it becomes a true star.

The Herschel Space Observatory captured this image of the Eagle nebula, with its intensely cold gas and dust. The "Pillars of Creation," made famous by the Hubble Space Telescope, are seen inside the circle. There are future stars embedded in dark filaments, and hot young stars are already illuminating the nebula to produce two bright regions. [Image: ESA/Herschel/PACS/SPIRE/Hill, Motte, HOBYS Key Programme Consortium]

But how could Herschel see through dust when other instruments couldn't?

Our eyes can't see through dust, and neither can telescopes that detect visible light. However, light comes in many wavelengths that are invisible to our eyes, including the longer wavelengths of infrared and submillimeter. These can penetrate dust, and also see the cooler part of the universe, such as the star-forming regions, which radiate at these wavelengths.

Earth-based telescopes can't detect this light because our atmosphere absorbs it. However, Herschel's sensitive instruments could see the entire spectrum of the far infrared and submillimeter radiation, the first telescope to do so.

Herschel was launched in May 2009 by the European Space Agency (ESA), the largest telescope ever sent into orbit. At 3.5 meters (about eleven and a half feet) the main mirror is 0.9 meter (almost three feet) greater in diameter than that of the Hubble Space Telescope.

The telescope was named for William and Caroline Herschel. They were German-born, but lived in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. William was the discoverer of the planet Uranus and also of infrared radiation. With the assistance of his sister Caroline, he laid the foundations for modern astronomy. Caroline, who was the first woman to be credited with the discovery of a comet, got her brother interested in nebulae. Together they surveyed the sky and cataloged the nebulae of the northern hemisphere.

The Herschel Space Observatory had been observing low-temperature objects to help us understand, amongst other things, how stars and galaxies form and evolve, and the chemistry of nebulae. On April 29, 2013 the mission ended when the infrared observatory finally exhausted its helium coolant.

You Should Also Read:

Herschel Museum of Astronomy

Astronomy ABC - H for Herschel Space Observatory

William Herschel

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Mona Evans. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Mona Evans. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.