Chilli - Dynamite in the Kitchen

Columbus had never seen one before, but the flavour – spicy, piquant, stimulating, decidedly warm if not downright fiery – reminded him of pepper, a spice more valuable than gold in Europe, which led him to christen the totally Mesoamerican chilli “pepper of the Indies”. He came across this “pepper” on a Caribbean island during his very first voyage to the “New World” and took its seeds home to Spain. It was self-pollinating and easy to grow, and could therefore be sold cheaply; it consequently spread steadily across the continent, although it never became a particular feature of European cuisine – pepperoncini appear in Italian dishes, paprika in Hungarian specialities, pimentón throughout Spain, but while it is difficult to imagine an Indian or Asian cookery devoid of chillies, a trawl through French provincial cooking for instance, in search of the Mesoamerican “pepper”, will prove a frustrating experience and produce few if any results.

The designation bestowed by Columbus, ie pepper, is still used to describe the gently flavoured, temperate members of the family, which we know today as “sweet” or “bell” peppers, but it is the Mexican name which has stuck to those which bear true heat, be it mild or blistering: “chilli”, from the Aztec Náhuatl language. “Chili” and particularly “chile” are often used - and the Mexicans themselves call it “chile” - but I personally always refer to a chilli by its Aztec name. Beyond this “family” title lies a whole world of gloriously idiosyncratic names, many of them whimsical, playful, even romantic - Facing Heaven, Little Raisin, Bird’s Eye, Peruvian Queen – or downright alarming, as in Naga Viper, African Devil and Trinidad Scorpion.

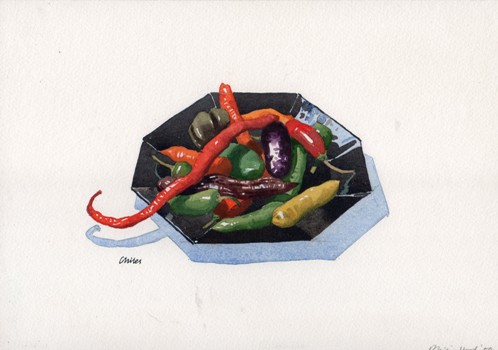

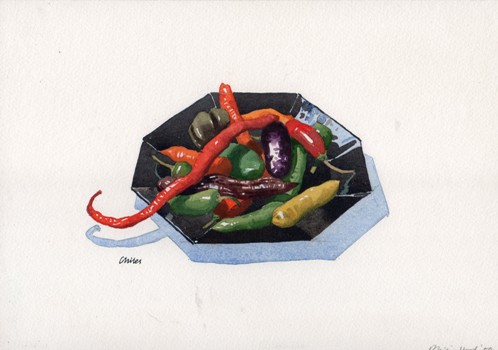

Chiles © Philip Hood

Chillies or capsicums belong to a notorious clan: the “Solanaceae” or “nightshades”, which include their other Mesoamerican kin, the potatoes, tomatoes and aubergines (eggplants), as well as tobacco, the more sinister mandrake and belladonna, and the innocuous looking petunia.

The earliest traces of wild chillies have been found in the Tehuacán valley of Mexico and date to around 7200 BC. Three different species however seem to have been cultivated in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica: Capsicum Pubescens, which was domesticated in Bolivia before migrating to Peru; Capsicum Baccatum, first grown in lowland Bolivia and now widely used throughout tropical South America; and the Capsicum Annuum, Chinense and Frutescens crowd which probably originated in the south of the continent but then made its way north to Mexico. It is this third group which is the ancestor of the modern chilli, particularly the Mexican Capsicum Annuum from which most of the chillies we cook with and eat in the 21st century are descended – although Capsicum Frutescens goes into the famous Tabasco sauce and the incandescent scotch bonnet or habanero chilli stems from Capsicum Chinense – and it was aboard the Spanish ships that the Mesoamerican chilli set out to conquer the world: the Peruvian “ají” sailed from the port of Callao, and from Acapulco on the western coast of Mexico, Capsicum Annuum put out to sea courtesy of the “Manila Galleons”, which plied their trade across the Pacific to the Philippines between 1565 and 1815. From Manila the chilli would have made its way across Asia and into the fragrant, aromatic cuisines of Thailand, Vietnam, Korea and China for instance.

To the east, the chilli would take the Atlantic route from the port of Veracruz to the Iberian Peninsula and then onwards across Europe, the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Middle East, travelling along the land trade routes and the major waterways. In Europe it was greeted as a botanical curiosity and was planted originally for its decorative value, until its spiciness began to rival that of its infinitely more valuable competitor, pepper.

The chilli is often misunderstood, lionised or abhorred for its heat alone. But this heat is just one of its many characteristics. Chillies come in all colours, shapes, sizes, textures, aromas and levels of piquancy; however, a chilli’s most crucial talent is not heat but flavour. There are hundreds of varieties of chilli, not only in its Mexican homeland but worldwide, many of them totally regional or even local, and each and every one has a flavour all of its own - it may take practice and experience to detect the differences, but they are most certainly there. Furthermore, a chilli’s individual flavour and heat, far from overwhelming the personality of any other foodstuffs with which it is combined and/or cooked as is often assumed, are capable of highlighting and bringing out their companions’ essences and aromas, together with nuances and shades of flavour which might otherwise be indiscernible.

Whatever their provenance and personal attributes, chillies do undoubtedly conceal a heart of fire, an exuberant and unbridled passion which fills every mouthful with excitement and power. Some offer just a gentle warmth, which lingers on the lips; others produce an instant explosion of heat, blotting out all thought and overwhelming the mind; all add spice, fragrance and a tremendous depth and complexity of flavour to whatever they are cooked with, for that is the quintessential nature of chillies. Their heat, whether blistering or mellow, is carried particularly within the seeds and veins or placenta of the fruit and is due to a chemical compound, capsaicin, a powerful irritant to the mucous membranes of the mouth – although it has an interesting reputation of stimulating the brain into releasing feel-good endorphins (presumably once the pain has subsided!).

However innocuous a chilli may look, the only truly reliable way to measure its heat is to taste it, as chillies of the same variety, grown in the same field and even on the same plant, can vary in pungency - but this method obviously carries very real dangers! It is worth noting that the smaller the chilli, the greater its fire, but for anybody whose palate retains the slightest sensitivity, a relatively trustworthy way of judging heat is crucial. In 1912, American pharmacist Wilbur Scoville came up with a “test” which consisted of a panel of tasters who gave chillies a score, and the consensus of scores was used to determine the heat. Needless to say, this did not produce unfailing results, and the Scoville Test underwent many changes and became increasingly scientific, until today it employs the incredibly technical sounding “high-performance liquid chromatography” to measure the capsaicin makeup of a chili pepper variety with considerable accuracy and give it a rating in “Scoville Heat Units” – which can run into millions. Luckily for those of us who simply want to know whether a specific chilli is likely to damage our palate for life, most chilli producers and suppliers now use a simple scale, from 1 to 10, to rate a chilli’s heat – 1 will impart a warm glow to your lips, while 10 will blow the roof off your mouth, so be sure to check the label before you take a bite!

The designation bestowed by Columbus, ie pepper, is still used to describe the gently flavoured, temperate members of the family, which we know today as “sweet” or “bell” peppers, but it is the Mexican name which has stuck to those which bear true heat, be it mild or blistering: “chilli”, from the Aztec Náhuatl language. “Chili” and particularly “chile” are often used - and the Mexicans themselves call it “chile” - but I personally always refer to a chilli by its Aztec name. Beyond this “family” title lies a whole world of gloriously idiosyncratic names, many of them whimsical, playful, even romantic - Facing Heaven, Little Raisin, Bird’s Eye, Peruvian Queen – or downright alarming, as in Naga Viper, African Devil and Trinidad Scorpion.

Chillies or capsicums belong to a notorious clan: the “Solanaceae” or “nightshades”, which include their other Mesoamerican kin, the potatoes, tomatoes and aubergines (eggplants), as well as tobacco, the more sinister mandrake and belladonna, and the innocuous looking petunia.

The earliest traces of wild chillies have been found in the Tehuacán valley of Mexico and date to around 7200 BC. Three different species however seem to have been cultivated in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica: Capsicum Pubescens, which was domesticated in Bolivia before migrating to Peru; Capsicum Baccatum, first grown in lowland Bolivia and now widely used throughout tropical South America; and the Capsicum Annuum, Chinense and Frutescens crowd which probably originated in the south of the continent but then made its way north to Mexico. It is this third group which is the ancestor of the modern chilli, particularly the Mexican Capsicum Annuum from which most of the chillies we cook with and eat in the 21st century are descended – although Capsicum Frutescens goes into the famous Tabasco sauce and the incandescent scotch bonnet or habanero chilli stems from Capsicum Chinense – and it was aboard the Spanish ships that the Mesoamerican chilli set out to conquer the world: the Peruvian “ají” sailed from the port of Callao, and from Acapulco on the western coast of Mexico, Capsicum Annuum put out to sea courtesy of the “Manila Galleons”, which plied their trade across the Pacific to the Philippines between 1565 and 1815. From Manila the chilli would have made its way across Asia and into the fragrant, aromatic cuisines of Thailand, Vietnam, Korea and China for instance.

To the east, the chilli would take the Atlantic route from the port of Veracruz to the Iberian Peninsula and then onwards across Europe, the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Middle East, travelling along the land trade routes and the major waterways. In Europe it was greeted as a botanical curiosity and was planted originally for its decorative value, until its spiciness began to rival that of its infinitely more valuable competitor, pepper.

The chilli is often misunderstood, lionised or abhorred for its heat alone. But this heat is just one of its many characteristics. Chillies come in all colours, shapes, sizes, textures, aromas and levels of piquancy; however, a chilli’s most crucial talent is not heat but flavour. There are hundreds of varieties of chilli, not only in its Mexican homeland but worldwide, many of them totally regional or even local, and each and every one has a flavour all of its own - it may take practice and experience to detect the differences, but they are most certainly there. Furthermore, a chilli’s individual flavour and heat, far from overwhelming the personality of any other foodstuffs with which it is combined and/or cooked as is often assumed, are capable of highlighting and bringing out their companions’ essences and aromas, together with nuances and shades of flavour which might otherwise be indiscernible.

Whatever their provenance and personal attributes, chillies do undoubtedly conceal a heart of fire, an exuberant and unbridled passion which fills every mouthful with excitement and power. Some offer just a gentle warmth, which lingers on the lips; others produce an instant explosion of heat, blotting out all thought and overwhelming the mind; all add spice, fragrance and a tremendous depth and complexity of flavour to whatever they are cooked with, for that is the quintessential nature of chillies. Their heat, whether blistering or mellow, is carried particularly within the seeds and veins or placenta of the fruit and is due to a chemical compound, capsaicin, a powerful irritant to the mucous membranes of the mouth – although it has an interesting reputation of stimulating the brain into releasing feel-good endorphins (presumably once the pain has subsided!).

However innocuous a chilli may look, the only truly reliable way to measure its heat is to taste it, as chillies of the same variety, grown in the same field and even on the same plant, can vary in pungency - but this method obviously carries very real dangers! It is worth noting that the smaller the chilli, the greater its fire, but for anybody whose palate retains the slightest sensitivity, a relatively trustworthy way of judging heat is crucial. In 1912, American pharmacist Wilbur Scoville came up with a “test” which consisted of a panel of tasters who gave chillies a score, and the consensus of scores was used to determine the heat. Needless to say, this did not produce unfailing results, and the Scoville Test underwent many changes and became increasingly scientific, until today it employs the incredibly technical sounding “high-performance liquid chromatography” to measure the capsaicin makeup of a chili pepper variety with considerable accuracy and give it a rating in “Scoville Heat Units” – which can run into millions. Luckily for those of us who simply want to know whether a specific chilli is likely to damage our palate for life, most chilli producers and suppliers now use a simple scale, from 1 to 10, to rate a chilli’s heat – 1 will impart a warm glow to your lips, while 10 will blow the roof off your mouth, so be sure to check the label before you take a bite!

You Should Also Read:

The Chillies of Mexico

The chillies of Mexico - El Jalapeño

The chillies of Mexico - El Serrano

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Isabel Hood. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Isabel Hood. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mickey Marquez for details.