Pluto Is a Dwarf Planet

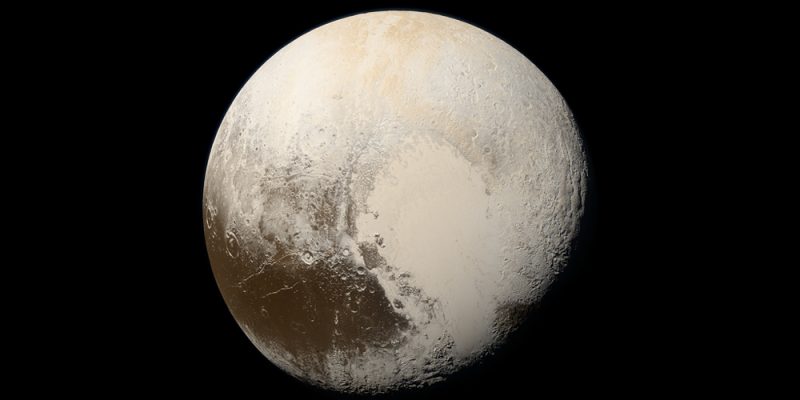

Pluto, as imaged by the New Horizons spacecraft

Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto at the Lowell Observatory, Arizona in 1930.

In 2006 the International Astronomical Union (IAU) announced a new classification system in which Pluto became a dwarf planet. Generations of schoolchildren knew its name as both the ninth planet and the Disney dog. They were dismayed.

Yet instead of asking why Pluto isn't a planet anymore, a more interesting question is: Why was Pluto ever thought to be a planet?

The story began with the planet Uranus. William Herschel discovered it in 1781, but by 1845 it was puzzling astronomers by not moving as expected.

French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier thought that the discrepancy was due to the gravitational pull of an undiscovered planet. His calculation of this planet's position allowed Johann Galle at the Berlin Observatory to locate Neptune in 1846.

Then half a century later it seemed that another large planet was disturbing the orbits of Neptune and Uranus. The hunt was on for a ninth planet. Perceval Lowell had made predictions about this Planet X, and after his death Lowell Observatory hired Tombaugh to look for it. The object he discovered on February 18, 1930 was assumed to be the missing planet.

However it was soon evident that Pluto was small. Over the years, each measurement of Pluto came up with an even smaller size. It was far too small to have any gravitational influence on Neptune.

Finally, in the 1990s scientists used a highly accurate space probe measurement of Neptune's mass to recalculate the orbits of the outer planets. It turned out that there was no anomaly. The orbits were as they should be if undisturbed by a Planet X. Finding Pluto was a lucky accident, though it's a tribute to Tombaugh's thoroughness that he spotted the tiny distant object.

Pluto is not only smaller than several solar system moons, but is also an icy body in an orbit very different to those of the eight planets. The planets and the objects in the asteroid belt orbit in the plane of the ecliptic, as though they were on a giant plate. Pluto's orbit is tilted to the ecliptic.

It seemed that Pluto was unique until 1992. Then the first discoveries of other small bodies beyond Neptune confirmed the existence of the Kuiper Belt. The Kuiper Belt contains hundreds of thousands of such icy bodies orbiting at a distance of between 30 and 50 AU. (An AU – astronomical unit – is the distance from the earth to the sun.)

The bodies orbiting beyond Neptune are commonly called trans-Neptunian objects. In 2005 the discovery of one that appeared to be larger than Pluto finally moved astronomers to define a planet. Considering the ensuing controversy, Eris (goddess of strife and discord) was an appropriate name for the new discovery.

We should realize that reclassifying heavenly objects isn't new. Eighteenth century German astronomer Johann Bode had suggested that there should be a planet between Mars and Jupiter, and the discovery of Ceres in 1801 seemed to confirm it. Unfortunately, half a century later, there were fifteen “planets” in this orbit. Astronomers decided they were a new class of objects, and they called them asteroids.

Interestingly, Ceres has now also been classified as a dwarf planet, along with Pluto and Eris and two other trans-Neptunian objects, Makemake and Haumea. Even some who are unconvinced that Pluto is a planet are puzzled by the dwarf planet class, especially since Ceres is quite different to the other four. They have been designated both as dwarf planets and plutoids.

However even if Pluto is not our ninth planet, it has still turned out to be the largest known member of an intriguing new class of solar system object.

Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto at the Lowell Observatory, Arizona in 1930.

In 2006 the International Astronomical Union (IAU) announced a new classification system in which Pluto became a dwarf planet. Generations of schoolchildren knew its name as both the ninth planet and the Disney dog. They were dismayed.

Yet instead of asking why Pluto isn't a planet anymore, a more interesting question is: Why was Pluto ever thought to be a planet?

The story began with the planet Uranus. William Herschel discovered it in 1781, but by 1845 it was puzzling astronomers by not moving as expected.

French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier thought that the discrepancy was due to the gravitational pull of an undiscovered planet. His calculation of this planet's position allowed Johann Galle at the Berlin Observatory to locate Neptune in 1846.

Then half a century later it seemed that another large planet was disturbing the orbits of Neptune and Uranus. The hunt was on for a ninth planet. Perceval Lowell had made predictions about this Planet X, and after his death Lowell Observatory hired Tombaugh to look for it. The object he discovered on February 18, 1930 was assumed to be the missing planet.

However it was soon evident that Pluto was small. Over the years, each measurement of Pluto came up with an even smaller size. It was far too small to have any gravitational influence on Neptune.

Finally, in the 1990s scientists used a highly accurate space probe measurement of Neptune's mass to recalculate the orbits of the outer planets. It turned out that there was no anomaly. The orbits were as they should be if undisturbed by a Planet X. Finding Pluto was a lucky accident, though it's a tribute to Tombaugh's thoroughness that he spotted the tiny distant object.

Pluto is not only smaller than several solar system moons, but is also an icy body in an orbit very different to those of the eight planets. The planets and the objects in the asteroid belt orbit in the plane of the ecliptic, as though they were on a giant plate. Pluto's orbit is tilted to the ecliptic.

It seemed that Pluto was unique until 1992. Then the first discoveries of other small bodies beyond Neptune confirmed the existence of the Kuiper Belt. The Kuiper Belt contains hundreds of thousands of such icy bodies orbiting at a distance of between 30 and 50 AU. (An AU – astronomical unit – is the distance from the earth to the sun.)

The bodies orbiting beyond Neptune are commonly called trans-Neptunian objects. In 2005 the discovery of one that appeared to be larger than Pluto finally moved astronomers to define a planet. Considering the ensuing controversy, Eris (goddess of strife and discord) was an appropriate name for the new discovery.

We should realize that reclassifying heavenly objects isn't new. Eighteenth century German astronomer Johann Bode had suggested that there should be a planet between Mars and Jupiter, and the discovery of Ceres in 1801 seemed to confirm it. Unfortunately, half a century later, there were fifteen “planets” in this orbit. Astronomers decided they were a new class of objects, and they called them asteroids.

Interestingly, Ceres has now also been classified as a dwarf planet, along with Pluto and Eris and two other trans-Neptunian objects, Makemake and Haumea. Even some who are unconvinced that Pluto is a planet are puzzled by the dwarf planet class, especially since Ceres is quite different to the other four. They have been designated both as dwarf planets and plutoids.

However even if Pluto is not our ninth planet, it has still turned out to be the largest known member of an intriguing new class of solar system object.

You Should Also Read:

Bode and Bode's Law

Eris and Pluto - They're Not Twins

Kuiper Belt

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Mona Evans. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Mona Evans. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.