Beagle 2 – Lost and Found

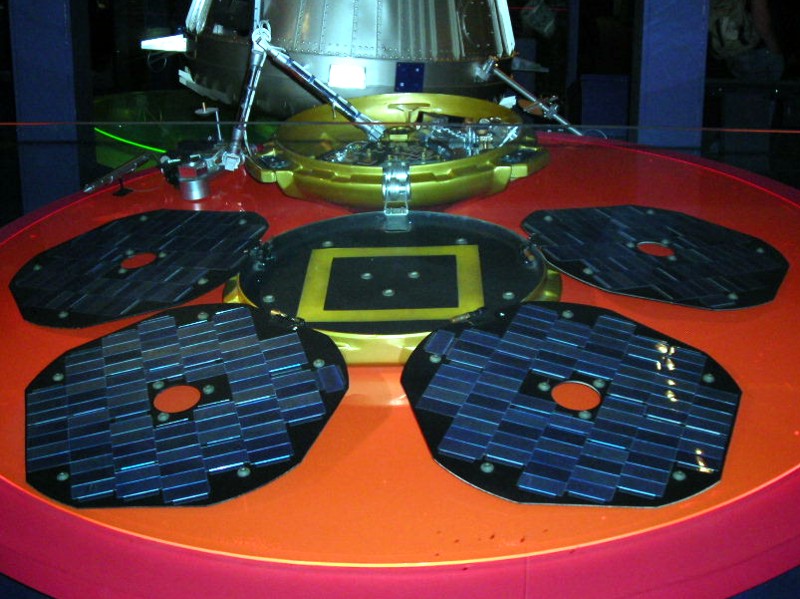

Model of Beagle 2 in the London Science Museum (Photos: Richard and Sharron Kruse, 2009)

Beagle 2 is a little British space probe that was lost on Mars one Christmas day, and not found for over a decade. The story began a bit like a gentle comedy where an eccentric with a dream wins the day against the odds. But it missed out the happy ending.

Background

In 1976 NASA put two spacecraft called Viking on Mars. The mission included testing for signs of life, but the results were inconclusive.

Fast forward to 1996. In August, worldwide headlines shouted that Martian life had been discovered – not on Mars, but on Earth. Martian meteorite ALH 84001 supposedly contained the evidence. Even the White House made a statement: “[Rock 84001] speaks of the possibility of life. If this discovery is confirmed, it will surely be one of the most stunning insights into our universe that science has ever uncovered.”

ALH 84001 is the most thoroughly studied meteorite ever discovered, but in the end few scientists were persuaded that it showed life on Mars. Yet it was a reminder that maybe it was time for a new astrobiology probe. Professor Colin Pillinger, a planetary scientist at Britain's Open University, was very keen. In 1997, when the European Space Agency (ESA) decided to launch an orbiter, Pillinger proposed that Mars Express should take a lander. And the lander should look for life. Within a few days his proposed lander had a name.

Beagle 2

Pillinger referred to his proposal as Beagle 2. But what was Beagle 1?

HMS Beagle was the ship on which Charles Darwin sailed to distant and inhospitable parts of the globe, discovering new species of plants and animals, both living and extinct. His observations and specimens set him to asking questions which eventually led to On the Origin of Species. Pillinger felt that a probe going to Mars looking for life might make discoveries that would raise questions as fundamental as those presented by Darwin's work.

If the lander were to piggyback on Mars Express, it would need to be cheap and light. It would need an innovative design to include the necessary tools within the weight limit of around 60 kg (130 lbs). Funding would be a problem, but they hoped that some could be raised from sponsorship. The whole plan would have to persuade both ESA and potential sponsors.

The organization

To design and build the probe and define its mission, there was a consortium which included academia and the British space industry. But since there was no committed funding, the organization was not very organized.

Yet the project caught the attention of many of people in Britain who liked the idea of a British probe. To build on the public interest, the Lander Operations Control Centre (LOCC) was located in the National Space Centre in Leicester in central England. Visitors could see what was going on in the control center when tests were carried out, and as Beagle worked on Mars.

Pillinger was enthusiastic, knowledgeable, witty, eccentric and personable. The journalists loved the media-savvy boffin with a dream, and he was good at keeping the story in the news. For example, you need to calibrate colors on Mars using a reference card. British artist Damien Hirst designed the test card.

Two members of the British pop group Blur wanted to get involved, and offered to write Beagle's call sign. When the probe landed, unfolded, raised its antenna and phoned home, the controllers would hear nine notes that are now part of Blur's “No Place to Run” single.

The plan

Despite the severe weight limit, in November of 1998 ESA's Science Programme Committee passed the consortium's design and experiment package. In 2000 a review committee declared it “eminently doable”.

Beagle's destination was Isidus Planitia, a flat basin that was relatively free of rocky debris. Beagle would use the sort of technology that Mars Pathfinder did in 1997, i.e., airbags and “hit, bounce, and roll”. But Pathfinder had 24 airbags, Beagle had only three. Although Pathfinder was much more massive than Beagle, three didn't leave much leeway.

After landing, Beagle's hinged cover would open, the solar panels would unfold and then the communications antenna could be raised to transmit the call sign. The mission was to last 180 Martian days. It would be examining geology and soil, and collecting data on the atmosphere, surface layers and climate, as well as looking for life signatures.

Christmas Day 2003

Mars Express was safely inserted into Mars orbit. It released Beagle 2 on December 19 at the appointed time. On Earth they listened for Beagle on Christmas Day. Then on Boxing Day (December 26). And into 2004. But on February 6 the mission was finally officially declared lost.

What went wrong?

Official inquiries produced long lists of things that might have failed. Most people assumed that the landing went wrong and that pieces of Beagle 2 littered the Martian landscape somewhere.

Lost and found

On January 16, 2015 the UK Space Agency announced that by studying images from the HiRise camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), Beagle 2 had been found on Isidus Planitia. Some of the possible things-that-may-have-gone-wrong could now be eliminated. The Beagle had landed. Unfortunately, since not all of the solar panels deployed, the antenna couldn't transmit. So near, and yet so far.

Colin Pillinger died in 2014, never knowing how very close his dream had come to being a reality.

Beagle 2 is a little British space probe that was lost on Mars one Christmas day, and not found for over a decade. The story began a bit like a gentle comedy where an eccentric with a dream wins the day against the odds. But it missed out the happy ending.

Background

In 1976 NASA put two spacecraft called Viking on Mars. The mission included testing for signs of life, but the results were inconclusive.

Fast forward to 1996. In August, worldwide headlines shouted that Martian life had been discovered – not on Mars, but on Earth. Martian meteorite ALH 84001 supposedly contained the evidence. Even the White House made a statement: “[Rock 84001] speaks of the possibility of life. If this discovery is confirmed, it will surely be one of the most stunning insights into our universe that science has ever uncovered.”

ALH 84001 is the most thoroughly studied meteorite ever discovered, but in the end few scientists were persuaded that it showed life on Mars. Yet it was a reminder that maybe it was time for a new astrobiology probe. Professor Colin Pillinger, a planetary scientist at Britain's Open University, was very keen. In 1997, when the European Space Agency (ESA) decided to launch an orbiter, Pillinger proposed that Mars Express should take a lander. And the lander should look for life. Within a few days his proposed lander had a name.

Beagle 2

Pillinger referred to his proposal as Beagle 2. But what was Beagle 1?

HMS Beagle was the ship on which Charles Darwin sailed to distant and inhospitable parts of the globe, discovering new species of plants and animals, both living and extinct. His observations and specimens set him to asking questions which eventually led to On the Origin of Species. Pillinger felt that a probe going to Mars looking for life might make discoveries that would raise questions as fundamental as those presented by Darwin's work.

If the lander were to piggyback on Mars Express, it would need to be cheap and light. It would need an innovative design to include the necessary tools within the weight limit of around 60 kg (130 lbs). Funding would be a problem, but they hoped that some could be raised from sponsorship. The whole plan would have to persuade both ESA and potential sponsors.

The organization

To design and build the probe and define its mission, there was a consortium which included academia and the British space industry. But since there was no committed funding, the organization was not very organized.

Yet the project caught the attention of many of people in Britain who liked the idea of a British probe. To build on the public interest, the Lander Operations Control Centre (LOCC) was located in the National Space Centre in Leicester in central England. Visitors could see what was going on in the control center when tests were carried out, and as Beagle worked on Mars.

Pillinger was enthusiastic, knowledgeable, witty, eccentric and personable. The journalists loved the media-savvy boffin with a dream, and he was good at keeping the story in the news. For example, you need to calibrate colors on Mars using a reference card. British artist Damien Hirst designed the test card.

Two members of the British pop group Blur wanted to get involved, and offered to write Beagle's call sign. When the probe landed, unfolded, raised its antenna and phoned home, the controllers would hear nine notes that are now part of Blur's “No Place to Run” single.

The plan

Despite the severe weight limit, in November of 1998 ESA's Science Programme Committee passed the consortium's design and experiment package. In 2000 a review committee declared it “eminently doable”.

Beagle's destination was Isidus Planitia, a flat basin that was relatively free of rocky debris. Beagle would use the sort of technology that Mars Pathfinder did in 1997, i.e., airbags and “hit, bounce, and roll”. But Pathfinder had 24 airbags, Beagle had only three. Although Pathfinder was much more massive than Beagle, three didn't leave much leeway.

After landing, Beagle's hinged cover would open, the solar panels would unfold and then the communications antenna could be raised to transmit the call sign. The mission was to last 180 Martian days. It would be examining geology and soil, and collecting data on the atmosphere, surface layers and climate, as well as looking for life signatures.

Christmas Day 2003

Mars Express was safely inserted into Mars orbit. It released Beagle 2 on December 19 at the appointed time. On Earth they listened for Beagle on Christmas Day. Then on Boxing Day (December 26). And into 2004. But on February 6 the mission was finally officially declared lost.

What went wrong?

Official inquiries produced long lists of things that might have failed. Most people assumed that the landing went wrong and that pieces of Beagle 2 littered the Martian landscape somewhere.

Lost and found

On January 16, 2015 the UK Space Agency announced that by studying images from the HiRise camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), Beagle 2 had been found on Isidus Planitia. Some of the possible things-that-may-have-gone-wrong could now be eliminated. The Beagle had landed. Unfortunately, since not all of the solar panels deployed, the antenna couldn't transmit. So near, and yet so far.

Colin Pillinger died in 2014, never knowing how very close his dream had come to being a reality.

You Should Also Read:

Christmas in the Skies

Top Five Dubious Astronomy Stories 2014

Good-bye Spirit

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Mona Evans. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Mona Evans. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.