Exploring the Apollo Landing Sites

When the last two men left the Moon at the end of 1972, they probably thought that someone would be back in a decade or so to clear up after them. Half a century on, they – and we – are still waiting. As a reminder of their exploits, we now have some impressive images of the six Apollo landing sites from Moon-orbiting probes that have photographed the abandoned equipment just where the astronauts left it all those years ago.

We owe most of these amazing views to NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which has been spinning around the Moon since June 2009. Its original mission was to spy out new landing sites for future astronauts. But even as LRO was snapping the surface, President Obama canceled the program which was supposed to take humans back to the Moon. Ironically, LRO's most memorable contribution has been surveying the old landing sites rather than spotting new ones.

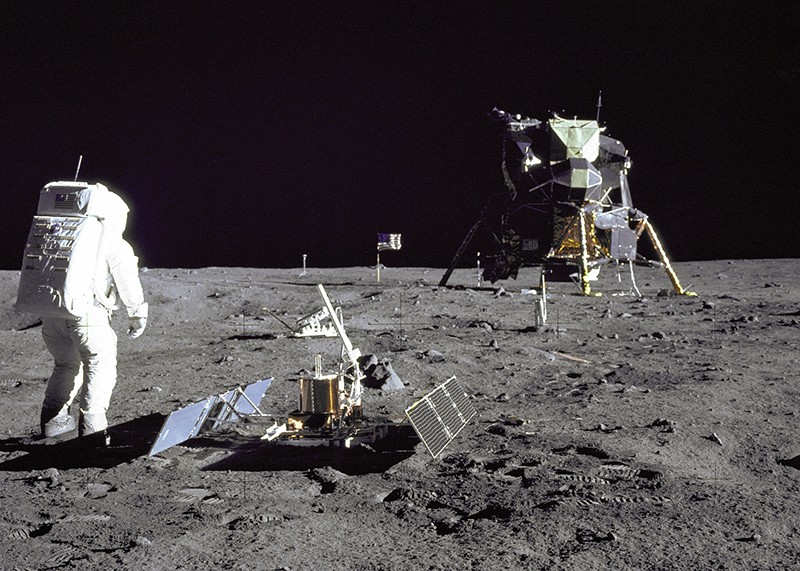

It all began at Tranquility Base on the Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility). Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed here in the lunar module Eagle on 20 July 1969. They were outside the lunar module for only about two hours, but they did plant a flag and set up experiments.

LRO took its first view of the site in July 2009, in time for the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing. A month later, LRO returned for a closer look. This time, in addition to the lunar module, it spotted equipment that Aldrin had put out on the surface, such as the lunar ranging retro reflector (LRRR) for bouncing laser beams to measure the distance to the Moon, and the passive seismic experiment (PSE) for detecting Moonquakes. A faint trail in the lunar dust marked Neil Armstrong's path to a nearby crater called Little West.

After the success of the first landing, NASA felt ready to aim for more interesting targets. One of my favorite Apollo missions was Apollo 12 in November 1969, which touched down a short walk away from an old unmanned probe, Surveyor 3. The Surveyor had landed two and a half years earlier inside a shallow crater on the lunar plain called Oceanus Procellarum.

LRO pictures released in September 2011 show the tracks made by Pete Conrad and Alan Bean as they walked from their lunar module Intrepid past three small impact craters, finally circling the crater rim to the dormant Surveyor 3. They snipped off the Surveyor's camera and brought it back to Earth, where it is on display in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, Washington.

The crew of ill-fated Apollo 13 ended up simply looping around the Moon and returning to Earth in the crippled spacecraft. Flights only resumed in January 1971 when Apollo 14 visited an area near the center of the Moon called Fra Mauro.

On this mission Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell were meant to walk from their lunar module, Antares, to the rim of an impact feature called Cone Crater, but it took them longer than expected. Unsure of their bearings, they took samples at a broken boulder nicknamed Saddle Rock before turning back. From the LRO pictures we can see they were only about 100 feet away from the rim of Cone Crater. If pictures this detailed had been available at the time, they could have pressed on and completed their climb.

The most spectacular landing site of all was that of Apollo 15 at the end of July 1971: Hadley Rille, a snaking valley carved out by a lava flow near the foot of the lunar Apennine mountains. This mission was the first to use a battery-powered Moon car, called the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV). It let the astronauts to explore a much wider area, including driving to the edge of the rille. LRO's view of the Apollo 15 landing area shows the lunar rover parked on one side of the lunar module Falcon, with some scientific experiments and a laser reflector on the other side.

The penultimate manned landing, Apollo 16, was the only Apollo mission to visit the lunar highlands, touching down near a crater called Descartes. This picture of the site from LRO was taken with the Sun almost directly overhead. The overhead lighting emphasizes the dark halos around the lunar module Orion and the lunar rover where John Young and Charles Duke churned up the soil with their feet.

Apollo 17 was the last and longest Apollo mission. Gene Cernan and Jack Schmitt spent 75 hours on the Moon. They drove for some 35 km (22 miles) around their landing site on the southeastern edge of Mare Serenitatis, between the Taurus Mountains and the crater Littrow. Some of LRO's most astonishingly detailed images are of the Apollo 17 site. An enlargement of the descent stage of their lunar module, Challenger, even shows the two Portable Life Support System backpacks (PLSS) from their Moon suits, discarded to save weight before take-off.

These LRO pictures remind us not only of the astronauts who risked their lives going to the Moon but the thousands of dedicated engineers, scientists and other unheralded workers who designed and built the craft that got them there and back safely. One day, tourists will visit the Moon to see for themselves these Apollo landing sites which are lasting monuments to the courage and ingenuity of those involved in one of the greatest achievements in the history of human exploration.

We owe most of these amazing views to NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which has been spinning around the Moon since June 2009. Its original mission was to spy out new landing sites for future astronauts. But even as LRO was snapping the surface, President Obama canceled the program which was supposed to take humans back to the Moon. Ironically, LRO's most memorable contribution has been surveying the old landing sites rather than spotting new ones.

It all began at Tranquility Base on the Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility). Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed here in the lunar module Eagle on 20 July 1969. They were outside the lunar module for only about two hours, but they did plant a flag and set up experiments.

LRO took its first view of the site in July 2009, in time for the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing. A month later, LRO returned for a closer look. This time, in addition to the lunar module, it spotted equipment that Aldrin had put out on the surface, such as the lunar ranging retro reflector (LRRR) for bouncing laser beams to measure the distance to the Moon, and the passive seismic experiment (PSE) for detecting Moonquakes. A faint trail in the lunar dust marked Neil Armstrong's path to a nearby crater called Little West.

After the success of the first landing, NASA felt ready to aim for more interesting targets. One of my favorite Apollo missions was Apollo 12 in November 1969, which touched down a short walk away from an old unmanned probe, Surveyor 3. The Surveyor had landed two and a half years earlier inside a shallow crater on the lunar plain called Oceanus Procellarum.

LRO pictures released in September 2011 show the tracks made by Pete Conrad and Alan Bean as they walked from their lunar module Intrepid past three small impact craters, finally circling the crater rim to the dormant Surveyor 3. They snipped off the Surveyor's camera and brought it back to Earth, where it is on display in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, Washington.

The crew of ill-fated Apollo 13 ended up simply looping around the Moon and returning to Earth in the crippled spacecraft. Flights only resumed in January 1971 when Apollo 14 visited an area near the center of the Moon called Fra Mauro.

On this mission Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell were meant to walk from their lunar module, Antares, to the rim of an impact feature called Cone Crater, but it took them longer than expected. Unsure of their bearings, they took samples at a broken boulder nicknamed Saddle Rock before turning back. From the LRO pictures we can see they were only about 100 feet away from the rim of Cone Crater. If pictures this detailed had been available at the time, they could have pressed on and completed their climb.

The most spectacular landing site of all was that of Apollo 15 at the end of July 1971: Hadley Rille, a snaking valley carved out by a lava flow near the foot of the lunar Apennine mountains. This mission was the first to use a battery-powered Moon car, called the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV). It let the astronauts to explore a much wider area, including driving to the edge of the rille. LRO's view of the Apollo 15 landing area shows the lunar rover parked on one side of the lunar module Falcon, with some scientific experiments and a laser reflector on the other side.

The penultimate manned landing, Apollo 16, was the only Apollo mission to visit the lunar highlands, touching down near a crater called Descartes. This picture of the site from LRO was taken with the Sun almost directly overhead. The overhead lighting emphasizes the dark halos around the lunar module Orion and the lunar rover where John Young and Charles Duke churned up the soil with their feet.

Apollo 17 was the last and longest Apollo mission. Gene Cernan and Jack Schmitt spent 75 hours on the Moon. They drove for some 35 km (22 miles) around their landing site on the southeastern edge of Mare Serenitatis, between the Taurus Mountains and the crater Littrow. Some of LRO's most astonishingly detailed images are of the Apollo 17 site. An enlargement of the descent stage of their lunar module, Challenger, even shows the two Portable Life Support System backpacks (PLSS) from their Moon suits, discarded to save weight before take-off.

These LRO pictures remind us not only of the astronauts who risked their lives going to the Moon but the thousands of dedicated engineers, scientists and other unheralded workers who designed and built the craft that got them there and back safely. One day, tourists will visit the Moon to see for themselves these Apollo landing sites which are lasting monuments to the courage and ingenuity of those involved in one of the greatest achievements in the history of human exploration.

You Should Also Read:

Moon Madness

In the Shadow of the Moon - film review

Luna - Earth's daughter

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Ian Ridpath. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.