Huitlacoche, the Truffle of Mexico

The expression “rainy season” takes on a whole new meaning in Mexico. It used to be quite short but climate change seems to be affecting it and resulting in an earlier start and a later finish – the May and September school holidays were always reliably sunny during my childhood, while nowadays they can be drizzly and grey. The real rainy season, however, is as wet can be. The rain falls from the sky in sheets so thick and solid that you can barely see across the street, and it is admirably punctual, to the point where you can almost set your watch by it and plan your day around it – it is a good idea to ensure that you are not out in the open in mid afternoon because you are sure to be caught out and drenched to the skin.

The rain of course brings fungi, and the summer and early autumn markets, particularly in the mountains, are full of wild mushrooms, from the more familiar varieties like ceps, morels, pieds de mouton, bright orange trompetitas (little trumpets) and chanterelles, to the incredibly sinister-looking huitlacoche, known as the Mexican truffle or Mexican caviar - evocative and seductive names for a fungus which has been considered a tremendous delicacy since pre-Columbian times, particularly among the Aztecs, and is much sought after. In English, however, huitlacoche (also spelled cuitlacoche) goes by the horribly unattractive name of “corn smut” or “devil’s corn”, and while it has been revered for its “life-giving” properties and has featured in the diets of Native Americans such as the Hopi and Zuni, in other countries, crops and corn cobs affected by the fungus are considered “diseased” and routinely destroyed.

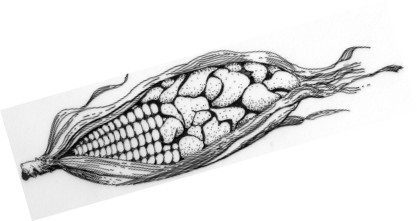

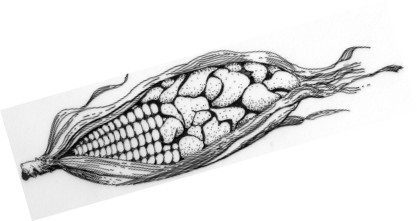

Huitlacoche, or Ustilago Maydis as it is known botanically, is quite simply a fungal infection of the corn cob and not a pretty sight. The “smut” grows from inside the corn kernels and blows them out into swollen, creepy black lobes covered in a silvery grey skin which crawl along the cob. I used to be terrified of it when I was small and no amount of bribes and threats would induce me to eat any dish containing it, but nowadays I truly regret my childhood fears because it is the most glorious-tasting wild mushroom of all – even though the back of my neck still prickles when I look at it, and my stomach churns lightly when its inky blood starts to flow across the pan and the whole fungus gradually breaks down into a thick, glossy, utterly slimy black purée. The flavour is almost impossible to pin down: definitely earthy, quite mushroomy, smoky in a damp campfire type of way, decidedly woodsy, faintly spicy with the barest hint of vanilla. The texture - if you can bring yourself to run your fingers over it – is silky and dry, with a softness rather like a slightly wet sponge.

Huitlacoche © Philip Hood

In the markets, the sellers pull the corn husks back and away from the cob to reveal and display the huitlacoche’s quality and pale grey freshness, as once it starts to darken and become shiny, it is past its prime and no housewife will touch it. The cob is sold with the fungus attached, and the street cooks advertise their corn smut repertoire by calling out to passers-by and trying to entice them to sample their huitlacoche quesadillas and tacos, soups and empanadas. The fungus seems to have a great affinity to specific Mexican ingredients like chillies, particularly the large, mild poblano chilli, and the herb epazote; and like all mushrooms, it marries deliciously with dairy products, as the 19th century Austrian chef to the imperial court of Maximilian and Carlota discovered when he filled very European crêpes with huitlacoche and poblanos braised in cream and thereby created one of modern Mexico’s most popular, distinctly post-Hispanic, and widely served seasonal dishes – “crepas de huitlacoche”.

Outside the rainy season, the only Mexican truffles available are in tins, and unlike genuine black truffles in jars, they work well in many dishes so I do not hesitate to use them occasionally. They obviously lack the haunting, magical mustiness of fresh huitlacoche, but cooked up with garlic, onions and a spicy chilli, they are very acceptable.

The following recipe has distinct European connotations, spicier and richer than its French counterpart, and a favourite market breakfast.

Dried epazote and tinned huitlacoche – San Miguel is a good brand - are available from Mexican grocers and mail order suppliers.

Scrambled eggs with Mexican truffles – Huevos revueltos con huitlacoche

Serves 2 generously

15 ml/1 tbsp olive oil

200 g/7 oz onions, peeled and coarsely chopped

1 garlic clove, peeled and finely sliced

1 green or red chilli, deseeded and finely sliced

5 ml/1 tsp dried epazote

1 x 400 g/14 oz tin huitlacoche

6 large eggs

60 ml/4 tbsp double/thick cream

25 g/1 oz butter

Warm corn tortillas, to serve (optional)

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Heat the oil in a large frying pan, add the onions, garlic, chilli, epazote and some seasoning, and cook over medium heat, stirring regularly, until it just starts to colour, about 10 minutes.

Stir in the huitlacoche, turn the heat right down, and simmer until most of the moisture has evaporated, about 15 minutes.

Whisk the eggs, cream and some seasoning in a bowl.

Melt the butter in a small frying pan and add the egg mixture. Cook over medium heat, stirring constantly, until the eggs just start to set but are still creamy. Gently fold in the huitlacoche and check the seasoning.

Divide between two warm plates and serve immediately with warm tortillas.

Buén provecho!

The rain of course brings fungi, and the summer and early autumn markets, particularly in the mountains, are full of wild mushrooms, from the more familiar varieties like ceps, morels, pieds de mouton, bright orange trompetitas (little trumpets) and chanterelles, to the incredibly sinister-looking huitlacoche, known as the Mexican truffle or Mexican caviar - evocative and seductive names for a fungus which has been considered a tremendous delicacy since pre-Columbian times, particularly among the Aztecs, and is much sought after. In English, however, huitlacoche (also spelled cuitlacoche) goes by the horribly unattractive name of “corn smut” or “devil’s corn”, and while it has been revered for its “life-giving” properties and has featured in the diets of Native Americans such as the Hopi and Zuni, in other countries, crops and corn cobs affected by the fungus are considered “diseased” and routinely destroyed.

Huitlacoche, or Ustilago Maydis as it is known botanically, is quite simply a fungal infection of the corn cob and not a pretty sight. The “smut” grows from inside the corn kernels and blows them out into swollen, creepy black lobes covered in a silvery grey skin which crawl along the cob. I used to be terrified of it when I was small and no amount of bribes and threats would induce me to eat any dish containing it, but nowadays I truly regret my childhood fears because it is the most glorious-tasting wild mushroom of all – even though the back of my neck still prickles when I look at it, and my stomach churns lightly when its inky blood starts to flow across the pan and the whole fungus gradually breaks down into a thick, glossy, utterly slimy black purée. The flavour is almost impossible to pin down: definitely earthy, quite mushroomy, smoky in a damp campfire type of way, decidedly woodsy, faintly spicy with the barest hint of vanilla. The texture - if you can bring yourself to run your fingers over it – is silky and dry, with a softness rather like a slightly wet sponge.

In the markets, the sellers pull the corn husks back and away from the cob to reveal and display the huitlacoche’s quality and pale grey freshness, as once it starts to darken and become shiny, it is past its prime and no housewife will touch it. The cob is sold with the fungus attached, and the street cooks advertise their corn smut repertoire by calling out to passers-by and trying to entice them to sample their huitlacoche quesadillas and tacos, soups and empanadas. The fungus seems to have a great affinity to specific Mexican ingredients like chillies, particularly the large, mild poblano chilli, and the herb epazote; and like all mushrooms, it marries deliciously with dairy products, as the 19th century Austrian chef to the imperial court of Maximilian and Carlota discovered when he filled very European crêpes with huitlacoche and poblanos braised in cream and thereby created one of modern Mexico’s most popular, distinctly post-Hispanic, and widely served seasonal dishes – “crepas de huitlacoche”.

Outside the rainy season, the only Mexican truffles available are in tins, and unlike genuine black truffles in jars, they work well in many dishes so I do not hesitate to use them occasionally. They obviously lack the haunting, magical mustiness of fresh huitlacoche, but cooked up with garlic, onions and a spicy chilli, they are very acceptable.

The following recipe has distinct European connotations, spicier and richer than its French counterpart, and a favourite market breakfast.

Dried epazote and tinned huitlacoche – San Miguel is a good brand - are available from Mexican grocers and mail order suppliers.

Scrambled eggs with Mexican truffles – Huevos revueltos con huitlacoche

Serves 2 generously

15 ml/1 tbsp olive oil

200 g/7 oz onions, peeled and coarsely chopped

1 garlic clove, peeled and finely sliced

1 green or red chilli, deseeded and finely sliced

5 ml/1 tsp dried epazote

1 x 400 g/14 oz tin huitlacoche

6 large eggs

60 ml/4 tbsp double/thick cream

25 g/1 oz butter

Warm corn tortillas, to serve (optional)

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Heat the oil in a large frying pan, add the onions, garlic, chilli, epazote and some seasoning, and cook over medium heat, stirring regularly, until it just starts to colour, about 10 minutes.

Stir in the huitlacoche, turn the heat right down, and simmer until most of the moisture has evaporated, about 15 minutes.

Whisk the eggs, cream and some seasoning in a bowl.

Melt the butter in a small frying pan and add the egg mixture. Cook over medium heat, stirring constantly, until the eggs just start to set but are still creamy. Gently fold in the huitlacoche and check the seasoning.

Divide between two warm plates and serve immediately with warm tortillas.

Buén provecho!

| Mexican Food Forum Posts |

| Basic Mexican Pasta - Fideo |

| Lard Making a Kitchen Comeback |

| Day of the Dead Question |

You Should Also Read:

Huitlacoche Quesadillas Recipe

Lenten Cooking in Mexico - Torta de Elote

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Isabel Hood. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Isabel Hood. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mickey Marquez for details.