The Day of the Dead in Mexico

The Day of the Dead – El Día de los Muertos - might have sent shivers down my spine as a child but it also brought with it a very special, deliciously ghoulish, annual treat. In late October, every sweet shop and street stall in Mexico City decks itself out in garlands of deep yellow marigolds known as cempasúchil, colourful tissue paper cut-outs of pumpkins and skeletons, and best of all, beautifully crafted sugar skulls with big toothy grins, shining eyes and names on their foreheads – they are wonderfully crunchy and achingly sweet, a treat to savour once a year and an opportunity to delight in the remembrance of one who has passed on. They are piled up in the markets in stacks at least a metre high, and the trick is to find one with your name – and if your name is not at least vaguely latino, you are not guaranteed a short and fruitful search! A trip to the bakery is another source of October excitement: the windows are packed with trays of pán de muerto (bread of the dead), a rich, sweet yeasted bread flavoured with aniseed and orange and sparkling with coloured sugar sprinkles. The traditional ones are round, but the more imaginative and skilled bakers shape theirs into infinitely more appealing skulls and bones, crosses and coffins, great floral wreaths, human and animal forms, even intricate lizards, alligators and beetles.

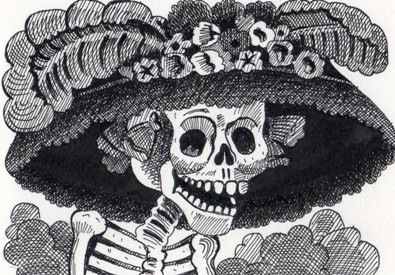

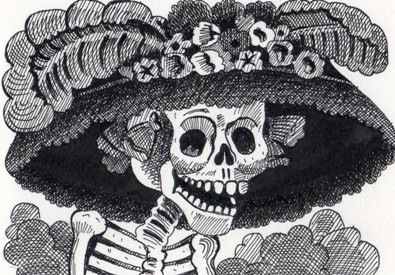

Mexicans excel at feasts and festivities, and virtually every day of the year is dedicated to a particular saint, with religious services, fireworks, and bands parading through the streets somewhere. The Día de Los Muertos, however, originated long before the arrival of the Conquistadores and Christianity, and takes pride of place - and far from being sombre or frightening, the occasion is noisy, exuberant and tremendous fun. Death goes by comical names like “La Huesuda”, the Bony One, “La Catrina”, the Fancy Lady, “La Pelona”, the Bald One; her skeleton is flamboyantly dressed and her face, often set beneath a white lace veil or a flower-decked hat, grins in the most fabulously macabre way. The festivities in fact span two days: November 1 is dedicated to departed children, while November 2 commemorates the adults. It is a time to remember and rejoice, to pay homage and honour those who are gone and show them that they are not forgotten, to call on the souls of the dead to return and spend a few hours with their living relatives.

La Catrina © Philip Hood

Altars are set up in the home in late October to summon the spirits and entice them back to the land of the living for a short autumnal visit, and traditionally feature the four elements: earth, represented by fruits and vegetables such as corn, beans and guavas; water, or even an alcoholic beverage like pulque, tequila or wine; tissue paper cut-outs to symbolise the wind; and the vividly coloured cempasúchil, or Aztec marigold, to embody fire. When the Days of the Dead arrive, the whole family prays at the altar in the evening before proceeding to the cemetery to spend time with the returning souls.

This graveyard vigil entails a considerable amount of cooking, as the dear departed must be welcomed back with plenty of food and drink to sustain them throughout their journey. Their favourite dishes are prepared and carried, together with their photograph and some personal possessions, to the cemetery where everything is set out by the grave on a small altar strewn with cempasúchil. Music is played and candles are lit to guide the spirits home to their loved ones, and then what a feast the living and the dead sit down to share in the crowded, candlelit graveyard! Pán de muerto fresh from the bakery, sugar skulls, crystallised pumpkin and sweet potato, bitter dark chocolate heavily laced with vanilla or cinnamon, rich savoury stews, stuffed chillies, tortillas filled with roast pork and baked with cream, cheese and a spicy sauce, vibrantly fresh salsas, tropical fruit, beer, tequila - whatever the dead person relished most in life. And as the candlelit night advances, the music becomes louder, the food and drink are consumed with increasing gusto, and the revellers, both alive and deceased, connect together again in celebration and merriment.

Pán de Muerto - Bread of the Dead

Makes 1 large round loaf

120 ml/1/2 cup milk

120 ml/1/2 cup water

100 g/4 oz unsalted butter, diced

800 g/1 3/4 lb strong white bread flour

10 g/1/3 oz dry yeast

5 ml/1 tsp salt

15 ml/1 tbsp whole anise or fennel seeds

100 g/4 oz caster/superfine sugar

Grated rind of 1 large orange

4 large eggs, beaten

For the orange glaze:-

100 g/4 oz caster/superfine sugar

Juice and grated rind of 1 large orange

Coloured sugar sprinkles

Heat the milk and water until steaming and remove from the heat. Add the butter and stir until it has melted. Cool to lukewarm before whisking in the orange rind and eggs.

Place the flour, yeast, salt, seeds and sugar in a large bowl and beat in the egg mixture with a wooden spoon. Turn the dough out on to the work surface and knead it until smooth. If it is very sticky, sprinkle in some more flour. Place in a lightly greased bowl, cover with a damp dish cloth and leave to rise in a warm corner of the kitchen until it has doubled in size, about one hour. Punch the dough back down, shape into a round loaf and place on a lightly oiled baking tray. Leave to rise again for one hour.

Preheat the oven to 180oC/350oF/gas 4/fan oven 160oC and bake the bread for 40 to 50 minutes, until golden – test for doneness by turning it out onto the work surface and tapping the underside, it should sound hollow.

Make the glaze while the bread is baking. Place all the ingredients in a small saucepan and heat gently, stirring to dissolve the sugar. Bring to the boil and simmer for 5 minutes.

When the bread is ready, pierce the surface with a skewer and, using a pastry brush, paint it with the glaze every five minutes or so until the glaze is used up. Dust with sugar sprinkles and leave to cool completely.

The bread will keep well in an airtight tin for up to five days.

Buén provecho!

Mexicans excel at feasts and festivities, and virtually every day of the year is dedicated to a particular saint, with religious services, fireworks, and bands parading through the streets somewhere. The Día de Los Muertos, however, originated long before the arrival of the Conquistadores and Christianity, and takes pride of place - and far from being sombre or frightening, the occasion is noisy, exuberant and tremendous fun. Death goes by comical names like “La Huesuda”, the Bony One, “La Catrina”, the Fancy Lady, “La Pelona”, the Bald One; her skeleton is flamboyantly dressed and her face, often set beneath a white lace veil or a flower-decked hat, grins in the most fabulously macabre way. The festivities in fact span two days: November 1 is dedicated to departed children, while November 2 commemorates the adults. It is a time to remember and rejoice, to pay homage and honour those who are gone and show them that they are not forgotten, to call on the souls of the dead to return and spend a few hours with their living relatives.

Altars are set up in the home in late October to summon the spirits and entice them back to the land of the living for a short autumnal visit, and traditionally feature the four elements: earth, represented by fruits and vegetables such as corn, beans and guavas; water, or even an alcoholic beverage like pulque, tequila or wine; tissue paper cut-outs to symbolise the wind; and the vividly coloured cempasúchil, or Aztec marigold, to embody fire. When the Days of the Dead arrive, the whole family prays at the altar in the evening before proceeding to the cemetery to spend time with the returning souls.

This graveyard vigil entails a considerable amount of cooking, as the dear departed must be welcomed back with plenty of food and drink to sustain them throughout their journey. Their favourite dishes are prepared and carried, together with their photograph and some personal possessions, to the cemetery where everything is set out by the grave on a small altar strewn with cempasúchil. Music is played and candles are lit to guide the spirits home to their loved ones, and then what a feast the living and the dead sit down to share in the crowded, candlelit graveyard! Pán de muerto fresh from the bakery, sugar skulls, crystallised pumpkin and sweet potato, bitter dark chocolate heavily laced with vanilla or cinnamon, rich savoury stews, stuffed chillies, tortillas filled with roast pork and baked with cream, cheese and a spicy sauce, vibrantly fresh salsas, tropical fruit, beer, tequila - whatever the dead person relished most in life. And as the candlelit night advances, the music becomes louder, the food and drink are consumed with increasing gusto, and the revellers, both alive and deceased, connect together again in celebration and merriment.

Pán de Muerto - Bread of the Dead

Makes 1 large round loaf

120 ml/1/2 cup milk

120 ml/1/2 cup water

100 g/4 oz unsalted butter, diced

800 g/1 3/4 lb strong white bread flour

10 g/1/3 oz dry yeast

5 ml/1 tsp salt

15 ml/1 tbsp whole anise or fennel seeds

100 g/4 oz caster/superfine sugar

Grated rind of 1 large orange

4 large eggs, beaten

For the orange glaze:-

100 g/4 oz caster/superfine sugar

Juice and grated rind of 1 large orange

Coloured sugar sprinkles

Heat the milk and water until steaming and remove from the heat. Add the butter and stir until it has melted. Cool to lukewarm before whisking in the orange rind and eggs.

Place the flour, yeast, salt, seeds and sugar in a large bowl and beat in the egg mixture with a wooden spoon. Turn the dough out on to the work surface and knead it until smooth. If it is very sticky, sprinkle in some more flour. Place in a lightly greased bowl, cover with a damp dish cloth and leave to rise in a warm corner of the kitchen until it has doubled in size, about one hour. Punch the dough back down, shape into a round loaf and place on a lightly oiled baking tray. Leave to rise again for one hour.

Preheat the oven to 180oC/350oF/gas 4/fan oven 160oC and bake the bread for 40 to 50 minutes, until golden – test for doneness by turning it out onto the work surface and tapping the underside, it should sound hollow.

Make the glaze while the bread is baking. Place all the ingredients in a small saucepan and heat gently, stirring to dissolve the sugar. Bring to the boil and simmer for 5 minutes.

When the bread is ready, pierce the surface with a skewer and, using a pastry brush, paint it with the glaze every five minutes or so until the glaze is used up. Dust with sugar sprinkles and leave to cool completely.

The bread will keep well in an airtight tin for up to five days.

Buén provecho!

You Should Also Read:

The Day of the Dead - Candied Pumpkin Recipe

Sweet Mexico - The Day of the Dead

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Isabel Hood. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Isabel Hood. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mickey Marquez for details.