Galileo's Daughter - book review

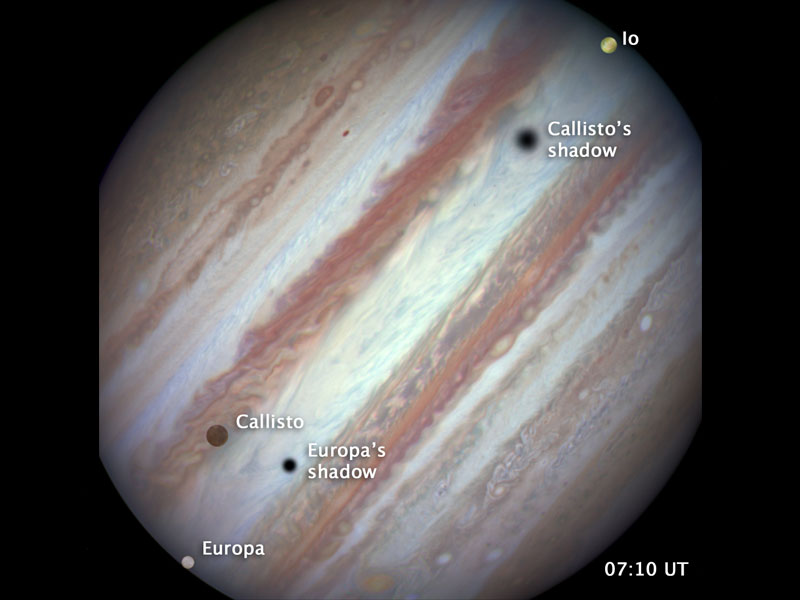

Three of the moons of Jupiter discovered by Galileo – they're known as the "Galilean moons". [NASA]

Who was Galileo? Most people would recognize the name of the man who is the symbol of the heroic voice of truth against a powerful reactionary Church. However this mythic Galileo is not the one Dava Sobel's book Galileo's Daughter reveals through his faith, his work and his daughter's love.

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) was born in Pisa. His family wasn't well off, though it was of minor nobility. When Galileo took up with a woman of a lower social class, he didn't marry her. They had three children for which he took responsibility when she married another man.

Concerned about the care of two daughters that wouldn't be marriageable due to their illegitimacy, Galileo put them into a convent. (This seems to have been a common way of looking after unmarriagable daughters in those days.) The daughter of the book's title was the elder one who chose the name Suor (Sister) Maria Celeste when she took her vows. Her letters show her devotion not only to God but also to the father whose celestial investigations are reflected in her chosen name. Galileo described her as “a woman of exquisite mind, singular goodness and most tenderly attached to me.”

Galileo's letters to his daughter were destroyed when she died. But most of her own letters survive, and they give a domestic touch to the story of the great man. She talks about mending his collars, making candied fruits to send him, or asking him to return a little basket. But she is also his support and his confidante when the Inquisition calls him.

The good

A comprehensive look at Galileo's life and times, work, and conflict with the Church would be many volumes. Nonetheless in one volume Sobel has looked at Galileo from many angles, including his relationship with his daughter, to tell his story.

Galileo's world was turbulent. The Thirty Years War was tearing Europe apart. Disease took rich and poor alike, and the Black Death would occasionally sweep terrifyingly through a region. Galileo himself suffered ill health for much of his life.

Galileo was a true Renaissance man – an inventor, mathematician, astronomer, experimental scientist, writer and thinker. To appreciate this essential part of him, Sobel explains some of his work and its importance. A reader without a science background may have to slow down for this, but it's worthwhile reading.

It's clear that Galileo didn't set out to oppose the Church. His writings show that he was a devout Catholic, and that he didn't see science conflicting with religion. He declared that “Holy Scripture cannot err.” Yet he felt that “though Scripture cannot err, its expounders and interpreters are liable to err in many ways,” such as a literal interpretation of figurative language. He couldn't understand why we had turn to Scripture for answers about things that we could discover for ourselves using our God-given faculties.

Sobel points out that although Galileo had enemies, there were many churchmen who supported him. In fact, Pope Urban VIII had once been a friend and supporter, telling Galileo that “men of great value like you deserve to live a long time to the benefit of the public.” However it wouldn't be politically sound for a pope to appear to be ignoring the Counter-Reformation position that only the Church could interpret scripture. This left Galileo's apparently (to modern eyes) reasonable position being heretical.

Some quibbles

Galileo is rightly considered the first experimental physicist. Instead of accepting what Aristotle (384 BC - 322 BC) had said about the natural world, he would actually test, observe and measure.

Unfortunately, the book includes the famous story of his dropping cannonballs off the tower of Pisa. Although they were of different weights, they landed pretty much together. According to Aristotle, the heavier one would land first. All very well, except that there aren't any contemporary accounts of Galileo's having done this, nor does he claim it in his own writings.

However there is a discussion of the experiments he did using balls rolling down an inclined plane. This produced motion slow enough to measure and his conclusions about falling bodies were based on these measurements.

In making Galileo more sympathetic, I felt that Sobel glossed over his arrogant side. He ridiculed his critics and although that may have amused his friends, it must have increased the enmity of his detractors. Yes, someone who denied Galileo's observations, but refused to look through a telescope, almost invited ridicule. However this may have led to an unforeseen consequence of the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.

In the Dialogue the case for an Earth-centered system is made by the character Simplicius, who always gets the worst of the argument. He's probably based on two of Galileo's main critics, including the one who shunned the telescope. However various historians think that Pope Urban VIII felt that he was the target since some of his arguments were included. This seems a believable reason for the pope to turn against Galileo, support the Inquisition, ban all of his works and keep him under house arrest for the rest of his life.

Worth reading?

This book is a great read, based on a wealth of research. I liked the way different elements of Galileo's life and work were woven together in a well-written narrative. It's informative, it's interesting – and it has a very touching ending.

Dava Sobel, Galileo's Daughter: A Drama of Science, Faith and Love, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0140280555

Note: I borrowed a copy of the book to write this review.

Who was Galileo? Most people would recognize the name of the man who is the symbol of the heroic voice of truth against a powerful reactionary Church. However this mythic Galileo is not the one Dava Sobel's book Galileo's Daughter reveals through his faith, his work and his daughter's love.

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) was born in Pisa. His family wasn't well off, though it was of minor nobility. When Galileo took up with a woman of a lower social class, he didn't marry her. They had three children for which he took responsibility when she married another man.

Concerned about the care of two daughters that wouldn't be marriageable due to their illegitimacy, Galileo put them into a convent. (This seems to have been a common way of looking after unmarriagable daughters in those days.) The daughter of the book's title was the elder one who chose the name Suor (Sister) Maria Celeste when she took her vows. Her letters show her devotion not only to God but also to the father whose celestial investigations are reflected in her chosen name. Galileo described her as “a woman of exquisite mind, singular goodness and most tenderly attached to me.”

Galileo's letters to his daughter were destroyed when she died. But most of her own letters survive, and they give a domestic touch to the story of the great man. She talks about mending his collars, making candied fruits to send him, or asking him to return a little basket. But she is also his support and his confidante when the Inquisition calls him.

The good

A comprehensive look at Galileo's life and times, work, and conflict with the Church would be many volumes. Nonetheless in one volume Sobel has looked at Galileo from many angles, including his relationship with his daughter, to tell his story.

Galileo's world was turbulent. The Thirty Years War was tearing Europe apart. Disease took rich and poor alike, and the Black Death would occasionally sweep terrifyingly through a region. Galileo himself suffered ill health for much of his life.

Galileo was a true Renaissance man – an inventor, mathematician, astronomer, experimental scientist, writer and thinker. To appreciate this essential part of him, Sobel explains some of his work and its importance. A reader without a science background may have to slow down for this, but it's worthwhile reading.

It's clear that Galileo didn't set out to oppose the Church. His writings show that he was a devout Catholic, and that he didn't see science conflicting with religion. He declared that “Holy Scripture cannot err.” Yet he felt that “though Scripture cannot err, its expounders and interpreters are liable to err in many ways,” such as a literal interpretation of figurative language. He couldn't understand why we had turn to Scripture for answers about things that we could discover for ourselves using our God-given faculties.

Sobel points out that although Galileo had enemies, there were many churchmen who supported him. In fact, Pope Urban VIII had once been a friend and supporter, telling Galileo that “men of great value like you deserve to live a long time to the benefit of the public.” However it wouldn't be politically sound for a pope to appear to be ignoring the Counter-Reformation position that only the Church could interpret scripture. This left Galileo's apparently (to modern eyes) reasonable position being heretical.

Some quibbles

Galileo is rightly considered the first experimental physicist. Instead of accepting what Aristotle (384 BC - 322 BC) had said about the natural world, he would actually test, observe and measure.

Unfortunately, the book includes the famous story of his dropping cannonballs off the tower of Pisa. Although they were of different weights, they landed pretty much together. According to Aristotle, the heavier one would land first. All very well, except that there aren't any contemporary accounts of Galileo's having done this, nor does he claim it in his own writings.

However there is a discussion of the experiments he did using balls rolling down an inclined plane. This produced motion slow enough to measure and his conclusions about falling bodies were based on these measurements.

In making Galileo more sympathetic, I felt that Sobel glossed over his arrogant side. He ridiculed his critics and although that may have amused his friends, it must have increased the enmity of his detractors. Yes, someone who denied Galileo's observations, but refused to look through a telescope, almost invited ridicule. However this may have led to an unforeseen consequence of the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.

In the Dialogue the case for an Earth-centered system is made by the character Simplicius, who always gets the worst of the argument. He's probably based on two of Galileo's main critics, including the one who shunned the telescope. However various historians think that Pope Urban VIII felt that he was the target since some of his arguments were included. This seems a believable reason for the pope to turn against Galileo, support the Inquisition, ban all of his works and keep him under house arrest for the rest of his life.

Worth reading?

This book is a great read, based on a wealth of research. I liked the way different elements of Galileo's life and work were woven together in a well-written narrative. It's informative, it's interesting – and it has a very touching ending.

Dava Sobel, Galileo's Daughter: A Drama of Science, Faith and Love, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0140280555

Note: I borrowed a copy of the book to write this review.

You Should Also Read:

Nicolaus Copernicus - the Revolution

Johannes Kepler - His Life

Tycho Brahe

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Mona Evans. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Mona Evans. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.