Mexico's Regional Gastronomies - Yucatán

The Yucatán Peninsula is Mexico’s big toe, curving around the Gulf of Mexico and then dipping south into the Caribbean. It was, and still is to a great extent, the land of the Maya, whose magnificent cities such as Chitchen Itzá, Uxmal, Calakmul and Tulum still stand today. Its history is turbulent, full of warfare and conflict, and although the Spaniards brought the whole area together into the Captaincy General of Yucatán, parts of the region broke away in later centuries and today the Yucatán consists of three separate sovereign states: Yucatán, Campeche and Quintana Roo.

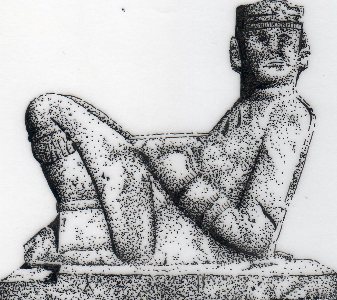

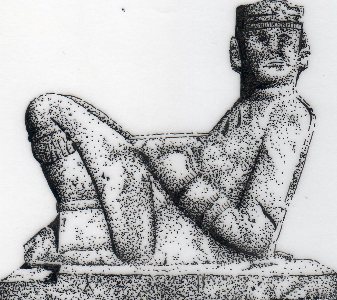

El Chacmool © Philip Hood

The area’s early isolation from the rest of the country noticeably influenced its culture and of course its food. It was not until the middle of the 20th century that effective communication by rail and then road was established with the capital and other parts of the country, and the Yucatán’s strongest commercial and cultural connections were created along sea rather than land routes. The United States across the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Islands and Cuba, Central and South America, even Europe have perhaps impacted the region far more powerfully than Mexico itself, resulting in what amounts in many ways to an individual, unique and separate nation, shaped by a very solid Maya identity blended with post-Hispanic and foreign additions. The area grew rich on the cultivation and export of henequén, a plant of the agave family from which rope and twine were made, and these trading links brought about the introduction of a wide variety of foodstuffs. I am always surprised when researching traditional Yucatecan gastronomy to come across very typical Mayan dishes like Pok Chuk, Dzotobichay and Salsa Xnipec alongside stuffed Dutch Edam cheese and a version of the Middle Eastern kibbeh contributed by Lebanese immigrants – what a fascinating melting pot!

Many of the time-honoured ingredients are native. The Yucatecan chillies are distinctive and seldom crop up in other regional Mexican cuisines: habanero, xcatik, chile seco de Yucatán. The predominant spice is achiote, earthy and faintly peppery, and meat or fish is marinated in a recado or paste made of its bright pink seeds. Sour oranges found their way into the region and then into the many salsas and guisados or stews, as well as the renowned sopa de lima or lime soup, and where the rest of Mexico wraps food in corn husks, Yucatecan cooks use fresh banana leaves – which also line the ancient pib or cooking pit. The beans are inky black like those of Veracruz and are traditionally served with pork on a Monday, while a pale green sauce of pumpkin seeds bathes the rather peculiar but delicious papadzules. Turkey is an everyday meal rather than a festive centre piece and tops salbutes and panuchos as well as being cooked in a dark, sinister looking sauce of roasted chillies. Ancient Mayan drinks are still consumed: aniseedy Xtabentún is based on the honey of bees which have fed on a member of the morning glory clan, while Balché is fermented in tree bark. The coastal cuisine is based on the wonderful abundance of fresh seafood and while a common thread runs through the kitchens of the whole peninsula, each of the three states has its own specialities which are well worth exploring.

My research into Yucatecan gastronomy has been exciting and rewarding, and I have been fascinated to discover a whole new world of Mexican dishes which I have not found in the rest of the country. There is a freshness, a sparkle and boldness to the food of this southern area which has truly delighted me.

The area’s early isolation from the rest of the country noticeably influenced its culture and of course its food. It was not until the middle of the 20th century that effective communication by rail and then road was established with the capital and other parts of the country, and the Yucatán’s strongest commercial and cultural connections were created along sea rather than land routes. The United States across the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Islands and Cuba, Central and South America, even Europe have perhaps impacted the region far more powerfully than Mexico itself, resulting in what amounts in many ways to an individual, unique and separate nation, shaped by a very solid Maya identity blended with post-Hispanic and foreign additions. The area grew rich on the cultivation and export of henequén, a plant of the agave family from which rope and twine were made, and these trading links brought about the introduction of a wide variety of foodstuffs. I am always surprised when researching traditional Yucatecan gastronomy to come across very typical Mayan dishes like Pok Chuk, Dzotobichay and Salsa Xnipec alongside stuffed Dutch Edam cheese and a version of the Middle Eastern kibbeh contributed by Lebanese immigrants – what a fascinating melting pot!

Many of the time-honoured ingredients are native. The Yucatecan chillies are distinctive and seldom crop up in other regional Mexican cuisines: habanero, xcatik, chile seco de Yucatán. The predominant spice is achiote, earthy and faintly peppery, and meat or fish is marinated in a recado or paste made of its bright pink seeds. Sour oranges found their way into the region and then into the many salsas and guisados or stews, as well as the renowned sopa de lima or lime soup, and where the rest of Mexico wraps food in corn husks, Yucatecan cooks use fresh banana leaves – which also line the ancient pib or cooking pit. The beans are inky black like those of Veracruz and are traditionally served with pork on a Monday, while a pale green sauce of pumpkin seeds bathes the rather peculiar but delicious papadzules. Turkey is an everyday meal rather than a festive centre piece and tops salbutes and panuchos as well as being cooked in a dark, sinister looking sauce of roasted chillies. Ancient Mayan drinks are still consumed: aniseedy Xtabentún is based on the honey of bees which have fed on a member of the morning glory clan, while Balché is fermented in tree bark. The coastal cuisine is based on the wonderful abundance of fresh seafood and while a common thread runs through the kitchens of the whole peninsula, each of the three states has its own specialities which are well worth exploring.

My research into Yucatecan gastronomy has been exciting and rewarding, and I have been fascinated to discover a whole new world of Mexican dishes which I have not found in the rest of the country. There is a freshness, a sparkle and boldness to the food of this southern area which has truly delighted me.

Chilli and Chocolate Stars of the Mexican Cocina by Isabel Hood is available from Amazon.co.uk | Just The Two of Us Entertaining Each Other by Isabel Hood is available from Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk |

You Should Also Read:

Mexico's Regional Gastronomy

Mexican Antojitos - Papadzules

The Sauces of Mexico - Yucatecan Salsa Xnipec

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Isabel Hood. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Isabel Hood. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mickey Marquez for details.