Historic Rootstock Vineyard Discovered

When Anton Nel took up his post as viticulture lecturer at Elsenburg Agricultural Institute he was allocated an office in a long one-storey brick building with a tin roof. His small office is at one end, the other has rows of steel benches with metal stools where students listen to lectures and do experiments. Between are small open concrete fermenting tanks, presses, de-stalkers and all the other equipment necessary for a winery.

The building, reached by a red mud road, is on the slope of a low hill surrounded by vines. Elsenburg is just north of Stellenbosch, in South Africa’s premium Cape winelands. It is here that tomorrow’s winemakers and viticulturists learn their trades.

Many different varieties are grown here in small blocks, open-air classrooms tended by students. Shiraz is next to Ruby Cabernet. Cinsaut alongside the almost extinct Pontac.

It’s coming to the end of summer and white grapes and early ripening black varieties have been harvested. I pick a large Cinsaut grape, taste it and look at its seeds. They are not yet brown which means they’re not ripe. “They need another week or two,” Anton tells me.

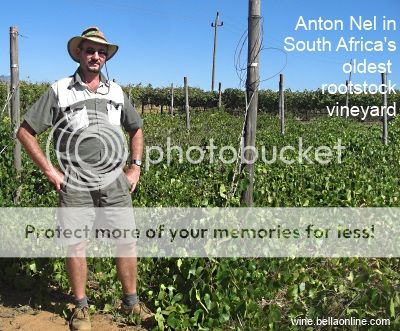

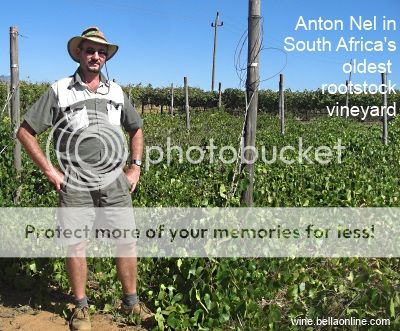

Among the blocks Anton found one that looked like a wasteland. The ground was covered with trailing vines of different sorts with unusually small leaves. There were tall posts but their trellising wires were broken. “When it became too overgrown they drove a cutter over the ground just slashing everything back,” said Anton.

Anton was intrigued by names, such as Rupestris du Lot and Riparia Gloria de Montpellier and codes including 333 EM, 4 401 and 107-11, scratched on metal tags on the posts. There are 24 rows of 12 vines. Eleven rows contain 6 of each of two varieties, meaning that 35 different varieties were planted here, though not all have survived.

Anton recognised names such Jacquez and Richter but others were unknown. He realised these strange forgotten plants were rootstock vines. But who planted them and why?

Rootstocks were – and remain – the solution to the destructive phylloxera bug that destroys the roots of the Vinifera wine grape species. Phylloxera spread from America to wipe out European vineyards in the second half of the 1800s. Native American vines co-exist with phylloxera, and it was realised that the only way to continue to make fine wines was to graft the fruit bearing part of Vinifera vines onto the roots of American vines. And that is what now happens in almost every vineyard in the world.

Just as there are many wine grape varieties, so there are many different rootstock vines, all descended from wild American vines. The challenge is to find the correct one to suit soil conditions where it is to be planted and to match the variety to be grafted on to it.

Phylloxera arrived in South Africa in 1886. Many experiments were made to find suitable rootstocks and rootstock vineyards were planted to supply grafting material.

Elsenburg was testing rootstock suitability and grafting vines on a large scale for the wine industry.

In 1937 Professor Chris Theron, who was the Dean of Oenology at Stellenbosch University and a lecturer at Elsenburg, decided to plant a library block of rootstock material at Elsenburg. This was intended to be a safeguard in case some future disaster struck the industry vineyards.

Anton Nel gained access to Professor Theron’s notebooks from his descendents and discovered Theron’s handwritten diagram of this backup rootstock vineyard. The names of the vines and their positions exactly matched the signs on the abandoned block.

“These vines have been abandoned for almost 80 years,” said Anton. “They’ve not been watered, manured, tended or pruned. It is the oldest rootstock vineyard in South Africa and there are varieties here that are unknown. Also, because of the habit then of planting seeds, some of the vines may not be as stated but unique.”

Anton has already installed irrigation, and will add fertiliser at the appropriate time. He has plans to identify the vines by DNA analysis. “It may be that we have a valuable resource here. Some of these old rootstocks might have very desirable qualities for the industry.”

As I took my leave baskets of purple Pinotage grapes were being unloaded from a trailer. Next to Anton’s office students were gathering to turn them into wine. “What happens to the finished wine?” I asked.

“It’s sold in bulk,” the winemaking instructor told me.

But I’ve heard that student winemakers hold the wildest parties at vintage time where no one ever has to ‘bring a bottle’.

Talk about wine on our forum.

Peter F May is the author of Marilyn Merlot and the Naked Grape: Odd Wines from Around the World which features more than 100 wine labels and the stories behind them, and PINOTAGE: Behind the Legends of South Africa’s Own Wine which tells the story behind the Pinotage wine and grape.

which features more than 100 wine labels and the stories behind them, and PINOTAGE: Behind the Legends of South Africa’s Own Wine which tells the story behind the Pinotage wine and grape.

The building, reached by a red mud road, is on the slope of a low hill surrounded by vines. Elsenburg is just north of Stellenbosch, in South Africa’s premium Cape winelands. It is here that tomorrow’s winemakers and viticulturists learn their trades.

Many different varieties are grown here in small blocks, open-air classrooms tended by students. Shiraz is next to Ruby Cabernet. Cinsaut alongside the almost extinct Pontac.

It’s coming to the end of summer and white grapes and early ripening black varieties have been harvested. I pick a large Cinsaut grape, taste it and look at its seeds. They are not yet brown which means they’re not ripe. “They need another week or two,” Anton tells me.

Among the blocks Anton found one that looked like a wasteland. The ground was covered with trailing vines of different sorts with unusually small leaves. There were tall posts but their trellising wires were broken. “When it became too overgrown they drove a cutter over the ground just slashing everything back,” said Anton.

Anton was intrigued by names, such as Rupestris du Lot and Riparia Gloria de Montpellier and codes including 333 EM, 4 401 and 107-11, scratched on metal tags on the posts. There are 24 rows of 12 vines. Eleven rows contain 6 of each of two varieties, meaning that 35 different varieties were planted here, though not all have survived.

Anton recognised names such Jacquez and Richter but others were unknown. He realised these strange forgotten plants were rootstock vines. But who planted them and why?

Rootstocks were – and remain – the solution to the destructive phylloxera bug that destroys the roots of the Vinifera wine grape species. Phylloxera spread from America to wipe out European vineyards in the second half of the 1800s. Native American vines co-exist with phylloxera, and it was realised that the only way to continue to make fine wines was to graft the fruit bearing part of Vinifera vines onto the roots of American vines. And that is what now happens in almost every vineyard in the world.

Just as there are many wine grape varieties, so there are many different rootstock vines, all descended from wild American vines. The challenge is to find the correct one to suit soil conditions where it is to be planted and to match the variety to be grafted on to it.

Phylloxera arrived in South Africa in 1886. Many experiments were made to find suitable rootstocks and rootstock vineyards were planted to supply grafting material.

Elsenburg was testing rootstock suitability and grafting vines on a large scale for the wine industry.

In 1937 Professor Chris Theron, who was the Dean of Oenology at Stellenbosch University and a lecturer at Elsenburg, decided to plant a library block of rootstock material at Elsenburg. This was intended to be a safeguard in case some future disaster struck the industry vineyards.

Anton Nel gained access to Professor Theron’s notebooks from his descendents and discovered Theron’s handwritten diagram of this backup rootstock vineyard. The names of the vines and their positions exactly matched the signs on the abandoned block.

“These vines have been abandoned for almost 80 years,” said Anton. “They’ve not been watered, manured, tended or pruned. It is the oldest rootstock vineyard in South Africa and there are varieties here that are unknown. Also, because of the habit then of planting seeds, some of the vines may not be as stated but unique.”

Anton has already installed irrigation, and will add fertiliser at the appropriate time. He has plans to identify the vines by DNA analysis. “It may be that we have a valuable resource here. Some of these old rootstocks might have very desirable qualities for the industry.”

As I took my leave baskets of purple Pinotage grapes were being unloaded from a trailer. Next to Anton’s office students were gathering to turn them into wine. “What happens to the finished wine?” I asked.

“It’s sold in bulk,” the winemaking instructor told me.

But I’ve heard that student winemakers hold the wildest parties at vintage time where no one ever has to ‘bring a bottle’.

Talk about wine on our forum.

Peter F May is the author of Marilyn Merlot and the Naked Grape: Odd Wines from Around the World

You Should Also Read:

Searching Texas for Munson

Munson Memorial Vineyard, Denison, Texas

Farewell to Pontac

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Peter F May. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Peter F May. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Peter F May for details.