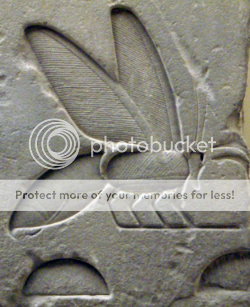

Honeybees Reject Pollen

Bee populations have captured the interest of scientific communities. Honeybees have started entombing seemingly viable hive cells filled with pollen for feeding their young. This behavior was first noticed in 2009. Interest to investigate the issue grew exponentially when it moved from being an anomaly to a common problem in 2011. Upon examination of the sealed off cells it was determined that each one contained unusually high levels of man-made chemicals. This discovery left scientists to ponder if the bees were actually detecting toxin levels so high, they would rather seal off the food source than risk exposure to the rest of the hive.

The cause for over exposure is likely from the well-intended attempt to eradicate the Varroa destructor mite. The population growth of this parasitic mite is explosive, as the mites feed on the larvae, pupa, and the bee itself. It becomes insidious by compromising the immune system at all stages of a bee’s life transmitting a multitude of viruses into its host, resulting in the deaths of entire colonies and the likely culprit of another scientific conundrum, Colony Collapse Disorder.

The mite was indigenous to Asia until its arrival into the mainstream bee population in the United States around 1990, first noticeably appearing in North Carolina. By the beginning of 2011 it is estimated to have destroyed over forty percent of the managed beehive populations in that state alone. It is believed that this pest is so prolific that it will singularly eradicate wild beehive populations altogether putting the survival of the honeybee squarely on beekeepers.

Bee pollination is essential for continued successful crop growth. It brings with it an estimated revenue stream of fifteen billion dollars throughout agricultural industries. America agriculture is very chemically driven to eradicate parasitic predators like the Varroa destructor. Farmers have to come up with new ideas each year in an attempt to outmaneuver this pest’s quick assimilation and resistance to pesticide, insecticide, and miticide treatments.

Biopesticides are generally considered less toxic than conventional pesticides. They contain more organic by-product than chemical and are now being explored with more frequency. To best manage pests in this manner reeducation needs to occur, teaching the vastly different distribution methods and the specificity of their effectiveness. When used with refined skill they are producing hopeful results as much as ninety-seven percent of an infestation is eradicated.

Honeybees are vital to the stability of our food supplies and agricultural economies. Without bee pollination nut bearing trees, fruits, vegetables, flowers, and herbs would show rapid depletion. It was discovered that the cotton shortage, 2009-2010, might have had more to do with bees not pollinating the plants due to the high use of pesticides than actual weather conditions or pest problems. When pesticide methods where changed the bees began, once again, to pollinate and cotton plants quickly rebounded.

This rudimentary evidence warrants that time, care, and due diligence be paid. A wise course of action would be to seek out longtime natural beekeepers and more closely study their organic methodology and modify our industrious nature toward a more cohesive working relationship that benefits both humans and bees.

The cause for over exposure is likely from the well-intended attempt to eradicate the Varroa destructor mite. The population growth of this parasitic mite is explosive, as the mites feed on the larvae, pupa, and the bee itself. It becomes insidious by compromising the immune system at all stages of a bee’s life transmitting a multitude of viruses into its host, resulting in the deaths of entire colonies and the likely culprit of another scientific conundrum, Colony Collapse Disorder.

The mite was indigenous to Asia until its arrival into the mainstream bee population in the United States around 1990, first noticeably appearing in North Carolina. By the beginning of 2011 it is estimated to have destroyed over forty percent of the managed beehive populations in that state alone. It is believed that this pest is so prolific that it will singularly eradicate wild beehive populations altogether putting the survival of the honeybee squarely on beekeepers.

Bee pollination is essential for continued successful crop growth. It brings with it an estimated revenue stream of fifteen billion dollars throughout agricultural industries. America agriculture is very chemically driven to eradicate parasitic predators like the Varroa destructor. Farmers have to come up with new ideas each year in an attempt to outmaneuver this pest’s quick assimilation and resistance to pesticide, insecticide, and miticide treatments.

Biopesticides are generally considered less toxic than conventional pesticides. They contain more organic by-product than chemical and are now being explored with more frequency. To best manage pests in this manner reeducation needs to occur, teaching the vastly different distribution methods and the specificity of their effectiveness. When used with refined skill they are producing hopeful results as much as ninety-seven percent of an infestation is eradicated.

Honeybees are vital to the stability of our food supplies and agricultural economies. Without bee pollination nut bearing trees, fruits, vegetables, flowers, and herbs would show rapid depletion. It was discovered that the cotton shortage, 2009-2010, might have had more to do with bees not pollinating the plants due to the high use of pesticides than actual weather conditions or pest problems. When pesticide methods where changed the bees began, once again, to pollinate and cotton plants quickly rebounded.

This rudimentary evidence warrants that time, care, and due diligence be paid. A wise course of action would be to seek out longtime natural beekeepers and more closely study their organic methodology and modify our industrious nature toward a more cohesive working relationship that benefits both humans and bees.

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Follow @WildlifeWelfare

Tweet

Content copyright © 2023 by Deb Duxbury. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Deb Duxbury. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Deb Duxbury for details.