Beer Color and the Beer Color Reference Guide

Evaluating the visual aspects of beer was, in my mind, one of the easiest profiles to describe. Being a very visual person, I believed in WYSIWYG, that is, what you see is what you get. I know to look for clarity, translucency, haze and opacity. Some haze is the result of chill, while others result from particles of yeast, ever present, suspended in the liquid or stirred up during the pour. Head varies, and can be described as creamy foam, large-and-small bubbles, chunky meringue, or a thin veil, and variable profiles in between. Color, however, is a little more difficult to determine. Beer judges need to be vigilant of the “halo effect,” the tendency to judge a beer based on one attribute. This attribute can have a positive or negative effect, and can result in over-evaluation or under-evaluation of a beer. Beer color can leave such a powerful subconscious impression on the observer that the sample can undergo an unfair bias. It is, therefore, important to assess all the attributes accurately. With a clear understanding of the factors that influence beer color and the Beer Color Reference Guide (https://www.beercolor.com/index.htm), the judge will be better able to assist the brewer in offering recommendations for correcting flaws in beer and producing a world-class product. During my attendance at regular weekly beer tastings, my journalistic compulsion prompts me to take copious notes during each session. Recording the title of each beer, the brewery, place of origin, "best by" date and ABV serves as the foundation for my file. Periodically, I review my descriptions of the head, lacing (“…lays like an intricate spider web on the inside of the crystal.”) or legs, clarity, and color. Of all the descriptors, color was recorded with the greatest degree of ambiguity. I noticed my descriptive included words such as gold, amber, chestnut, and black – not exactly imaginative, or terribly descriptive.

During my attendance at regular weekly beer tastings, my journalistic compulsion prompts me to take copious notes during each session. Recording the title of each beer, the brewery, place of origin, "best by" date and ABV serves as the foundation for my file. Periodically, I review my descriptions of the head, lacing (“…lays like an intricate spider web on the inside of the crystal.”) or legs, clarity, and color. Of all the descriptors, color was recorded with the greatest degree of ambiguity. I noticed my descriptive included words such as gold, amber, chestnut, and black – not exactly imaginative, or terribly descriptive.

Then I received a video from Dr. Lee Williams in Moses Lake, Washington, USA. In this video, a university professor was illustrating the fact that we see exactly what we expect to see. In this video, six people appear on-screen. Three are dressed in white shirts and black pants; three have black shirts and black pants. Two basketballs are to be passed within the groups who are milling about. The observer is instructed to count how many times the ball passes from white-shirt to white-shirt. I counted seventeen. At the end of the video, the professor asks if anyone saw something unusual in the film. About half raised their hands.

When he replayed it, he asked that you only watch the film, without counting passes. In the middle of the video, a person in an ape suit walked into the middle of the crowd, faced the camera and flexed its muscles. I was so stunned that I replayed the first video to see if the ape really appeared in the initial film. The professor’s point was this: When we expect a result, we often miss the obvious.

Color, a psychological and physiological evaluation of the light waves that enter the eye, is determined by the brain and its perception of a limited range of frequencies in the electromagnetic spectrum. Mark Schiess of Beer Color Laboratory points out that evaluation of beer color can vary, based on multiple factors, and may not be recorded as the true SRM value. Your perception is based on the quality and type of light available, the angle at which the sample is held, background, size and depth of the sample, bubbles or turbidity, foam, and characteristics of the container itself. Add the differences in genetics, and it is easy to understand that you may not “see” the same beer color as a person sitting next to you.

To complicate things more, color is observed in two ways – as reflected light (e.g., ink on paper) or transmitted light (computer screen). In reflected light, black is the result of an object absorbing all wavelengths – the resultant reflection appears to be black (CMYK – cyan + magenta + yellow = black). In transmitted light, white is the result of the merging of all wavelengths (RGB – red + green + blue).

Background can affect perception to a large degree. If you place a light object or color on a dark background, for example, it will appear much brighter than it actually is. This is demonstrated most clearly in Adleson’s Same Color Illusion, also known as the checker shadow illusion. It was created in 1995 by Edward H. Adelson, Professor of Vision Science at MIT. This optical illusion consists of black and white squares in a checkered pattern, with a green cylinder placed upon the checkered pattern. The green cone casts a shadow over a portion of the surface. The black and white blocks vary, and are, in actuality, different shades of gray. The white square in the shade is actually the same color and tone as the black square in the light. Your eye denies this, even when you are told of the fact. To further demonstrate this, Professor Adelson displays the next photo with a continuous connection between the two blocks. The demonstration is astounding, and serves as a strong lesson that color perception in beer may be acceptable to the eye, but may actually be inappropriate for the style of beer.

Although malt is the most important factor that influences the color of beer, other factors influence the final result, as well. Beer may be crafted based on Reinheitsgebot, or it may have the addition of adjuncts or additives. Not only can beer vary in color due to malt or extract type, hops used, and yeast affects, but also due to water chemistry, aging, boil times, oxidation, fining, and a list of other factors, including the environment in which it is viewed. Clear beer appears lighter than nebulous or turbid beer.

Two color samples can match when viewed under one light source, but you may find them to be very different under another light source. This is called metamerism. Explained in simple terms, this is most clearly demonstrated by the example in which a person puts on two socks of the same color, but realizes that one is black, and the other brown, when observed under different light. Metamerism may be a result of illumination, the genetic makeup of the observer, or geometric (caused by the angle at which a color is observed, including how far apart your eyes are.)

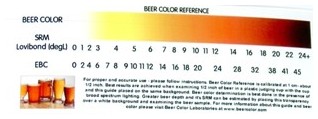

Evaluation of beer color is complicated further by the scale used. Joseph Williams Lovibond developed the first practical instrument for measuring color in beer. Degrees Lovibond, expressed as °L, is determined by comparing beer color to a series of glass slides.  Standard Reference Method (SRM) is a scale used to classify the color of beer in the USA. It is based on the Lovibond Scale. In 1958, the American Society of Brewing Chemists adopted standard spectrophometric measurements using ½ inch of solution and a light wavelength of 430 nm, a wavelength that corresponds to ultraviolet or ultra powder blue.

Standard Reference Method (SRM) is a scale used to classify the color of beer in the USA. It is based on the Lovibond Scale. In 1958, the American Society of Brewing Chemists adopted standard spectrophometric measurements using ½ inch of solution and a light wavelength of 430 nm, a wavelength that corresponds to ultraviolet or ultra powder blue.

The British Institute of Brewing Studies and the European Brewing Convention (EBC) used a different method to arrive at color. Originally, they examined their sample under a light wavelength of 530 nm (or green wavelength), but modified it in 1992 with a 1 cm sample and 430 nm. Although formulas exist to convert one scale to the other, the EBC and SRM methods are not related linearly, so conversions of one measure to another are not fully accurate.

In the USA, SRM is generally used for beer, and °L for grain. However, since °L has a greater error factor, many color references refer to the ASBC SRM.

For the beer judge, homebrewer, or small commercial brewery that does not have the advantage of expensive equipment, an accurate scale has been developed by Beer Color Laboratory in Carmel, Indiana as an easy-to-use, cost-effective tool to accurately determine beer color. It is called the Beer Color Reference Guide, and has evolved over the course of four years, into an accurate and useful guide that can measure beers from the lightest to the darkest ranges. The tool itself is transparent. The user is instructed to assess ½ “ (or approximately 1 cm) of beer in a plastic judging cup, with the cup and the guide placed on the same background under broad spectrum lighting. If beer depth is greater, the guide should be placed on a white background, and the beer sample examined in an elevated position.

Many portable reference guides have been manufactured, but this one is, by far, the most accurate. The transparent film does not interfere with color guidance the way ink on paper may be altered by the brightness of paper. Paper grade may vary from yellow to blue-gray, and can affect how color is observed. In addition, peering through a ½” sample of beer allows the lightest or darkest beers to be examined in a scale that is more one-dimensional, and thus, more accurate.

For more information, contact Beer Color Laboratories at:

https://www.beercolor.com/index.htm

Factors that can affect Beer Color:

Cheers!

Photos are: Beer Color Reference Guide by Beer Color Laboratory; Beer Color Reference Guide Wallet-sized Version

You Should Also Read:

Beer Tasting Tips - Assessing Appearance

Beer Tasting Tips - Impression & Drinkability

Beer Evaluation - Kinesthetic & Trigeminal Senses

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Carolyn Smagalski. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Carolyn Smagalski. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Carolyn Smagalski for details.