Alcohol Content of Wine

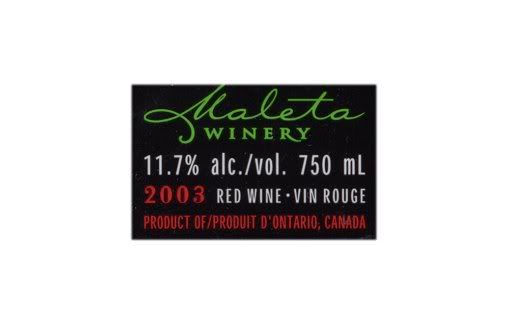

All wine contains alcohol. That is a basic definition of wine and wine laws require that the amount of alcohol present in the wine is declared*. There are certain differences about how this is done around the world. Trade agreements are working to having standardised wine labels so a label that is legal in one country can be exported to another, but there is still some way to go.

Nearly all wine labels state the alcohol content by percentage of volume. So a wine label that says 13% abv shows the wine is 13% pure alcohol by volume. The larger the number, the higher the alcohol. Most wines fall between 12 and 14 percent, though it can be as low as 8.5% from some German wines and as high as 15% (or more!) for bruisers from the New World. Fortified wines – which are wines which have had alcohol added – such as Port and Sherry can reach 18-19% abv.

But the abv on the label is not the entire story. Wineries are allowed a 1.5% leeway in displaying the abv. So a wine labelled as 14% abv could in fact contain up to 15.5% abv. There are several good reasons for this being legal, related to variances in the finished product and accuracy of measurements, which I won’t go into here. But since higher tax rates are levied on wines that exceed 14% abv you will not be surprised if wines marked as 14% abv have more of a tendency to exceed that level rather than be less alcoholic.

There is an oddity in the EU. For reasons I do not understand, the EU require that abv must be expressed to the nearest whole or half percentage. So a wine that is 13.8% abv cannot legally be labelled with this number but must be shown as 14% abv – and the consumer may think that it is actually higher. Crazy law.

A frequent comment on wine discussion boards is about wines that do not state the alcohol level at all. In the USA a wine whose label bears the words Table Wine and is between 7-14% abv does not need to show the alcohol level. This is a boon for small wineries producing non-vintage wines because they can print a large batch of labels and re-use them year after year, thus saving printing costs and also avoiding the bureaucratic and costly exercise of annually submitting labels for pre-approval to the relevant authorities.

Do you need to know the alcohol level of wines? I think so for a couple of reasons. Wines can vary so much in strength that you need to pace your drinking to avoid excess. I know several people who check labels when buying wine and will not purchase a bottle they consider too alcoholic.

Another reason is that, in the absence of other information, it can indicate the sweetness level. For a non-fortified wine, the lower the alcohol the more likelihood is that it is a sweet wine. That alcohol comes from the sugar in the wine. If all the sugar has been converted to alcohol then the wine will be dry. If fermentation is stopped before completion then there will be more sugar left in the wine. Conversely, if a sweet wine such as Port is intended, then fermentation is stopped by the addition of pure alcohol – a process known as fortification – and the wine’s abv is nearer 20% abv.

* Note: Yes, there are wines that have had all their alcohol removed by technical processes. Are these de-alcoholised wines worthy of the name wine? Make your feelings known in our discussion forum, Click the ‘Forum’ button to the right.

Peter F May is the author of Marilyn Merlot and the Naked Grape: Odd Wines from Around the World which features more than 100 wine labels and the stories behind them, and PINOTAGE: Behind the Legends of South Africa’s Own Wine which tells the story behind the Pinotage wine and grape.

which features more than 100 wine labels and the stories behind them, and PINOTAGE: Behind the Legends of South Africa’s Own Wine which tells the story behind the Pinotage wine and grape.

Nearly all wine labels state the alcohol content by percentage of volume. So a wine label that says 13% abv shows the wine is 13% pure alcohol by volume. The larger the number, the higher the alcohol. Most wines fall between 12 and 14 percent, though it can be as low as 8.5% from some German wines and as high as 15% (or more!) for bruisers from the New World. Fortified wines – which are wines which have had alcohol added – such as Port and Sherry can reach 18-19% abv.

But the abv on the label is not the entire story. Wineries are allowed a 1.5% leeway in displaying the abv. So a wine labelled as 14% abv could in fact contain up to 15.5% abv. There are several good reasons for this being legal, related to variances in the finished product and accuracy of measurements, which I won’t go into here. But since higher tax rates are levied on wines that exceed 14% abv you will not be surprised if wines marked as 14% abv have more of a tendency to exceed that level rather than be less alcoholic.

There is an oddity in the EU. For reasons I do not understand, the EU require that abv must be expressed to the nearest whole or half percentage. So a wine that is 13.8% abv cannot legally be labelled with this number but must be shown as 14% abv – and the consumer may think that it is actually higher. Crazy law.

A frequent comment on wine discussion boards is about wines that do not state the alcohol level at all. In the USA a wine whose label bears the words Table Wine and is between 7-14% abv does not need to show the alcohol level. This is a boon for small wineries producing non-vintage wines because they can print a large batch of labels and re-use them year after year, thus saving printing costs and also avoiding the bureaucratic and costly exercise of annually submitting labels for pre-approval to the relevant authorities.

Do you need to know the alcohol level of wines? I think so for a couple of reasons. Wines can vary so much in strength that you need to pace your drinking to avoid excess. I know several people who check labels when buying wine and will not purchase a bottle they consider too alcoholic.

Another reason is that, in the absence of other information, it can indicate the sweetness level. For a non-fortified wine, the lower the alcohol the more likelihood is that it is a sweet wine. That alcohol comes from the sugar in the wine. If all the sugar has been converted to alcohol then the wine will be dry. If fermentation is stopped before completion then there will be more sugar left in the wine. Conversely, if a sweet wine such as Port is intended, then fermentation is stopped by the addition of pure alcohol – a process known as fortification – and the wine’s abv is nearer 20% abv.

* Note: Yes, there are wines that have had all their alcohol removed by technical processes. Are these de-alcoholised wines worthy of the name wine? Make your feelings known in our discussion forum, Click the ‘Forum’ button to the right.

Peter F May is the author of Marilyn Merlot and the Naked Grape: Odd Wines from Around the World

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Peter F May. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Peter F May. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Peter F May for details.