Mystery of Enzymes for Brewing Beer

In my younger years, I found chemistry to be a little creepy. As one of the requirements in high school, chemistry seemed to be something foreign and abstract, like parabolas and theorems. No one told us we could use our chemistry knowledge in brewing beer, baking bread, or removing the chalk-like oxidation from our little red Mustangs.

In my younger years, I found chemistry to be a little creepy. As one of the requirements in high school, chemistry seemed to be something foreign and abstract, like parabolas and theorems. No one told us we could use our chemistry knowledge in brewing beer, baking bread, or removing the chalk-like oxidation from our little red Mustangs.

The instructor was a rookie, newly graduated from college and sorely lacking in the social skills needed to engage a roomful of juniors and seniors. At one point, she slammed a chemistry book down on her desk and shouted, “Damn you kids! I’m not teaching you anymore!” as she folded her arms and turned her back to the class.

She precipitated her own punishment. The class burst into laughter. Her action was like an enzyme, a catalyst that lowered the amount of energy needed for a reaction. Who knew? It could have been so simple.

That’s what enzymes do in brewing. Enzymes are little catalysts – or action figures – that lower the amount of activation energy needed for a reaction to occur. They are proteins that are the movers-and-shakers that initiate chemical reactions in life, but each has its own job. If you flick a light switch, you get the light, for example; the light switch won’t make your car start (at least, I hope not).

If you are a brewer, you may brew exclusively with malt extracts. These extracts have already advanced through the mashing process, making starches and sugars available for fermentation with no fuss and no bother to you. But at some point, you may want greater control over the final results of your brew. You will take that all-important step and scale-up to all-grain brewing. Basic knowledge of enzymes and how they work is the key to success.

Enzymes in brewing overcome static energy levels and help malts move through transitional states. Some are active in readying the malts to grow into plants (before malt is dried) or to create beer (after malt is dried).

Others work at different temperatures during mashing, the point at which water is added to cracked malts for conversion into starches and sugars. Some enzymes attack the starch walls, undressing the sugars trapped in the malt and exposing them to the action of the yeast. Different temperatures during mashing allow enzymes to degrade the proteins (proteolytic enzymes) or to degrade the starches (diastatic enzymes).

Yeast need amino acid proteins, but these are not available until the proteolytic enzymes do their work. Beta Glucanase releases the starch from the endosperm, and prevents the gums from creating a doughy bread rather than beer. This is best activated at temperatures between 95-113° F. Peptidase produces Free Amino Nitrogen (FAN). In other words, it breaks down nitrogen based proteins into amino acid proteins that are used as nutrients (food) for the yeast while they are busy working (eating the sugars). Peptidase activation happens between 115-131° F. At the same time and temperature, protease breaks down the large proteins that cause haze in beer. Protease also helps to create good beer head – one that is thick, moussy, creamy, sticky and long-lasting. Diastatic enzymes work to dissolve starches and convert them into fermentable and unfermentable sugars. Alpha amylase, activated between 149-160° F, breaks up the long branched sugars at each branch. Glucose and fructose (single molecules) are easily fermented. These are called monosaccharides. Maltose (a chain of 2 glucose molecules) and Maltriose (a chain of 3 glucose molecules) are also highly fermentable. Dextrose (a chain of 4 glucose molecules) does not break down at this temperature and is too complex for the little yeast. It cannot be easily fermented, so it remains in beer to give it body and residual sweetness. These higher temperatures result in beers with a fuller mouthfeel and lower alcohol levels.

Diastatic enzymes work to dissolve starches and convert them into fermentable and unfermentable sugars. Alpha amylase, activated between 149-160° F, breaks up the long branched sugars at each branch. Glucose and fructose (single molecules) are easily fermented. These are called monosaccharides. Maltose (a chain of 2 glucose molecules) and Maltriose (a chain of 3 glucose molecules) are also highly fermentable. Dextrose (a chain of 4 glucose molecules) does not break down at this temperature and is too complex for the little yeast. It cannot be easily fermented, so it remains in beer to give it body and residual sweetness. These higher temperatures result in beers with a fuller mouthfeel and lower alcohol levels.

Beta amylase creates wort that is more fermentable by breaking the chains into one, two, or three molecules. These enzymes are activated at lower temperatures, between 140-149° F. They will result in creating beer that is more highly attenuated, lighter in body and higher in alcohol content.

After sparging, all the steps remain the same as in extract brewing, so carry on!

Cheers!

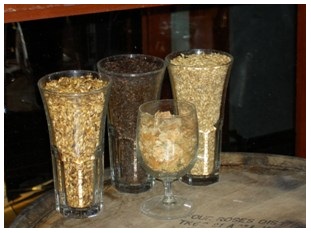

Photos are: Mashing-in; Caramel, Black Patent, and Pilsner Malts with hops in the foreground (In the wine glass)

Ready to mash? Outdoors may work well for you

Electric Brew Heater w/ 11" Element

Ready for bigger things?

10 Gallon Polar Ware All Grain Equipment Kit

You Should Also Read:

Competitive Homebrewing

Homebrewing - Books & Resources - Novice to Expert

Philadelphia Water Works - Help for Homebrewers

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Carolyn Smagalski. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Carolyn Smagalski. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Carolyn Smagalski for details.