Retsina

I was sitting by the harbour side at a rickety wooden table, perched on the weaved raffia seat of an ancient chair. It was hot and the ferry boat I was to catch was delayed. Well, perhaps not delayed but it was running on Greek time and I hadn’t been in the country long enough to adjust my clock to that slower pace of life.

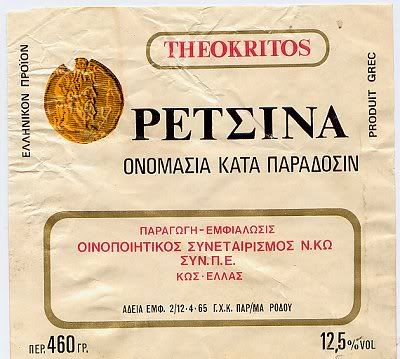

I got out a book and called for a glass of white wine. The owner brought what looked like a bottle of beer and a stubby glass. He flipped off the beer cap and poured a couple of inches of – not beer – but white wine. Condensation coated the side of the glass and the amount of water coating the pint sized bottle loosened the label which was sliding down the glass. I peeled it off. It read PÓTSINA.

The label from my first Retsina

A saucerful of fat black olives had appeared and after chewing the juicy berry a trail of oil ran down my chin. I took a swig of the ice cold wine. At that moment I had my epiphany. I loved PÓTSINA, or Retsina as we know it.

Our travel company representative, who met us first time visitors at Athens airport and took us to our first night’s hotel, gave us just two warnings: don’t drink Retsina – it’s for locals and you won’t like it– and always tell restaurants that you don’t want any olive oil on your salad ‘for your stomach’s sake’.

My lunch arrived. A fish simply cooked whole, its dead eyes looking reproachfully at me, surrounded by irregular sized fried potatoes. I had earlier seen an old women sitting on the step at the side of the taverna, her skirts pulled up and a bowl of large earthy potatoes clamped between her legs. She was peeling them, so I knew my chips were not from the freezer. As he put down a salad the proprietor tapped my shoulder and pointed at an old man sitting on the dockside repairing his nets. The fisherman waved back when he was hailed as the proprietor gestured at the fish on my plate. So the fish was fresh also. I had forgotten to decline oil on my salad and the bright red tomato chunks and knobbly green cucumber slices dotted with olives and pepper was swimming in green tinted thick golden olive oil. I loved the food, the oil and the Retsina. The wine was crisp, very crisp, dry and it had an intriguing tang and it so matched the food. Another bottle was called for and I was sad to leave when the ferry eventually arrived. I tucked the Retsina label in my book.

They say Retsina is an acquired taste. But if you like dry acidic wines you might well grow to love Retsina as much as I do. For me it evokes happy days on Greek islands. With the best imagination in the world, it is not the same on a cold miserable day back home.

Retsina is not the name of a grape, or a place on a map. It is a name for a style of wine made in Greece. It can be red or pink but is usually white. The distinguishing feature is that it is scented with pine wood. While wine drinkers are used to wines that taste of oak wood, and indeed think of oak as a feature of the better wines, pine has never caught on.

But in ancient Greece pine resin was used to seal earthenware containers that held wine and locals grew to like flavours that it imparted to wine.

Nowadays that pine tang comes from the addition of pine resin while making the wine.

I think the best Retsina is made on the islands, local wines generously flavoured with pine resin and bottled in pint beer bottles closed with a crown cap and meant for immediate drinking ice cold on scorching hot days.

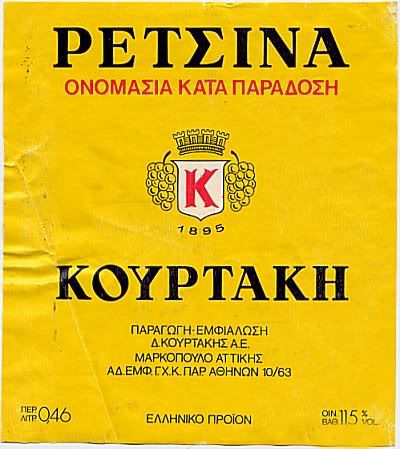

You can buy Retsina in most large wine outlets but these are export brands with pretensions, such as Kourtaki and Boutari, who have toned down the resin in the forlorn hope that non- Retsina lovers will buy them.

If you have never tried Retsina and cannot wait till you get to Greece, try it with Greek food which it so matches. Ask for a glass with your meze in a Greek restaurant. And let me know if it has gained another fan.

Cheers

Peter F May is the author of Marilyn Merlot and the Naked Grape: Odd Wines from Around the World which features more than 100 wine labels and the stories behind them, and PINOTAGE: Behind the Legends of South Africa’s Own Wine which tells the story behind the Pinotage wine and grape.

which features more than 100 wine labels and the stories behind them, and PINOTAGE: Behind the Legends of South Africa’s Own Wine which tells the story behind the Pinotage wine and grape.

I got out a book and called for a glass of white wine. The owner brought what looked like a bottle of beer and a stubby glass. He flipped off the beer cap and poured a couple of inches of – not beer – but white wine. Condensation coated the side of the glass and the amount of water coating the pint sized bottle loosened the label which was sliding down the glass. I peeled it off. It read PÓTSINA.

The label from my first Retsina

A saucerful of fat black olives had appeared and after chewing the juicy berry a trail of oil ran down my chin. I took a swig of the ice cold wine. At that moment I had my epiphany. I loved PÓTSINA, or Retsina as we know it.

Our travel company representative, who met us first time visitors at Athens airport and took us to our first night’s hotel, gave us just two warnings: don’t drink Retsina – it’s for locals and you won’t like it– and always tell restaurants that you don’t want any olive oil on your salad ‘for your stomach’s sake’.

My lunch arrived. A fish simply cooked whole, its dead eyes looking reproachfully at me, surrounded by irregular sized fried potatoes. I had earlier seen an old women sitting on the step at the side of the taverna, her skirts pulled up and a bowl of large earthy potatoes clamped between her legs. She was peeling them, so I knew my chips were not from the freezer. As he put down a salad the proprietor tapped my shoulder and pointed at an old man sitting on the dockside repairing his nets. The fisherman waved back when he was hailed as the proprietor gestured at the fish on my plate. So the fish was fresh also. I had forgotten to decline oil on my salad and the bright red tomato chunks and knobbly green cucumber slices dotted with olives and pepper was swimming in green tinted thick golden olive oil. I loved the food, the oil and the Retsina. The wine was crisp, very crisp, dry and it had an intriguing tang and it so matched the food. Another bottle was called for and I was sad to leave when the ferry eventually arrived. I tucked the Retsina label in my book.

They say Retsina is an acquired taste. But if you like dry acidic wines you might well grow to love Retsina as much as I do. For me it evokes happy days on Greek islands. With the best imagination in the world, it is not the same on a cold miserable day back home.

Retsina is not the name of a grape, or a place on a map. It is a name for a style of wine made in Greece. It can be red or pink but is usually white. The distinguishing feature is that it is scented with pine wood. While wine drinkers are used to wines that taste of oak wood, and indeed think of oak as a feature of the better wines, pine has never caught on.

But in ancient Greece pine resin was used to seal earthenware containers that held wine and locals grew to like flavours that it imparted to wine.

Nowadays that pine tang comes from the addition of pine resin while making the wine.

I think the best Retsina is made on the islands, local wines generously flavoured with pine resin and bottled in pint beer bottles closed with a crown cap and meant for immediate drinking ice cold on scorching hot days.

You can buy Retsina in most large wine outlets but these are export brands with pretensions, such as Kourtaki and Boutari, who have toned down the resin in the forlorn hope that non- Retsina lovers will buy them.

If you have never tried Retsina and cannot wait till you get to Greece, try it with Greek food which it so matches. Ask for a glass with your meze in a Greek restaurant. And let me know if it has gained another fan.

Cheers

Peter F May is the author of Marilyn Merlot and the Naked Grape: Odd Wines from Around the World

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Peter F May. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Peter F May. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Peter F May for details.